November 22, 2025

4 minute read

5 graphs show climate progress as the Paris Agreement turns 10 years old

The 2015 Paris Agreement paved the way for the world to avoid worst-case climate change scenarios. Here's where we are 10 years later

Ten years ago, the world came together to find a way out of climate emergency in the form of a global treaty called Paris Agreement.

Under the agreement, countries pledged to keep global temperatures “well below” a rise of two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and aim to limit the rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius. These goals were ambitious and required that greenhouse gas emissions begin to decline by 2025.

However, emissions continue to rise. Annual negotiations to implement the Paris Agreement continued over the past two weeks at this year's United Nations Climate Change Conference, or COP30, in Brazil, where participants recognized two simultaneous truths: We have made significant strides in protecting our planet, but huge leaps are still needed to avoid worse outcomes. These jumps are scary considering that President Donald Trump is once again withdrawing the United States from the agreement and that countries like China and Saudi Arabia are also still struggling to keep fossil fuels in the energy mix. China, however, is quickly overtaking the United States as a source of renewable energy, with solar and wind power showing exponential growth worldwide in recent years.

About supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism. subscription. By purchasing a subscription, you help ensure a future of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

These five charts show why the Paris Agreement is vital and how the world is moving forward 10 years later.

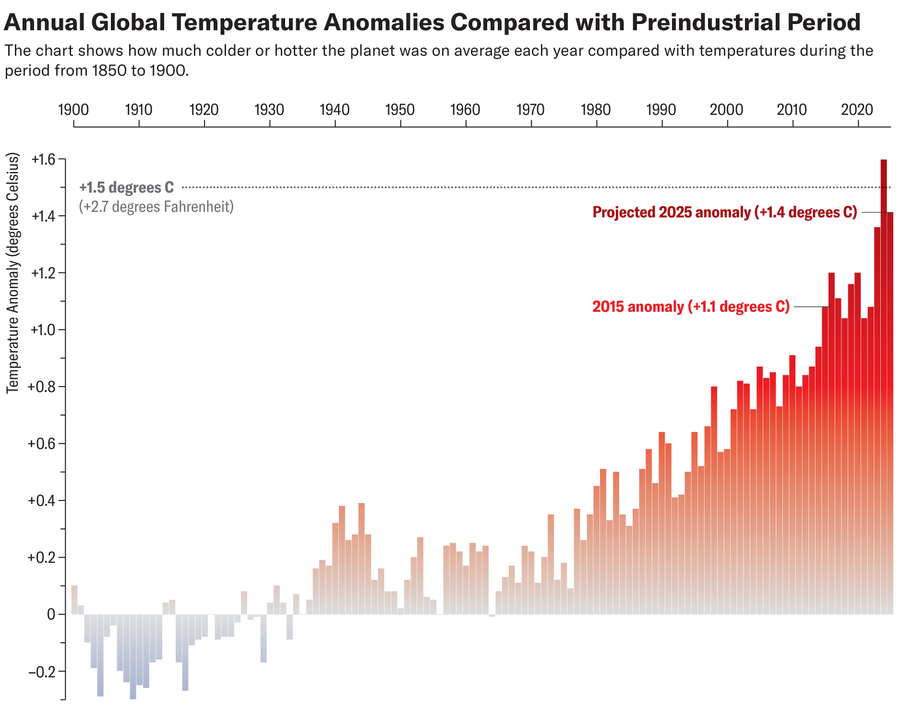

The Paris Agreement is based on an increase in temperature above an unspecified pre-industrial baseline, usually taken for the second half of the 19th century. Every year since 1970—more than half a century—temperatures have risen above average and risen rapidly.

In 2015, the average global temperature was 1.1 degrees higher than pre-industrial levels. Today it is about 1.3 degrees Celsius. (IN 2024 is the hottest year on record— the temperature on the planet was above 1.5 degrees Celsius, but the Paris Agreement considers the average over many years. The World Meteorological Organization predicts that 2025 will be about 1.4 degrees above pre-industrial average levels, making it the second or third hottest year on record.)

The increase is grim, but that's not the end of the story— especially if humans can stop climate pollution fast enough to reverse the warming trend. “Every ton counts; Every tenth of a degree is important; is important every year,” says Costa Samaras, an energy policy expert at Carnegie Mellon University.

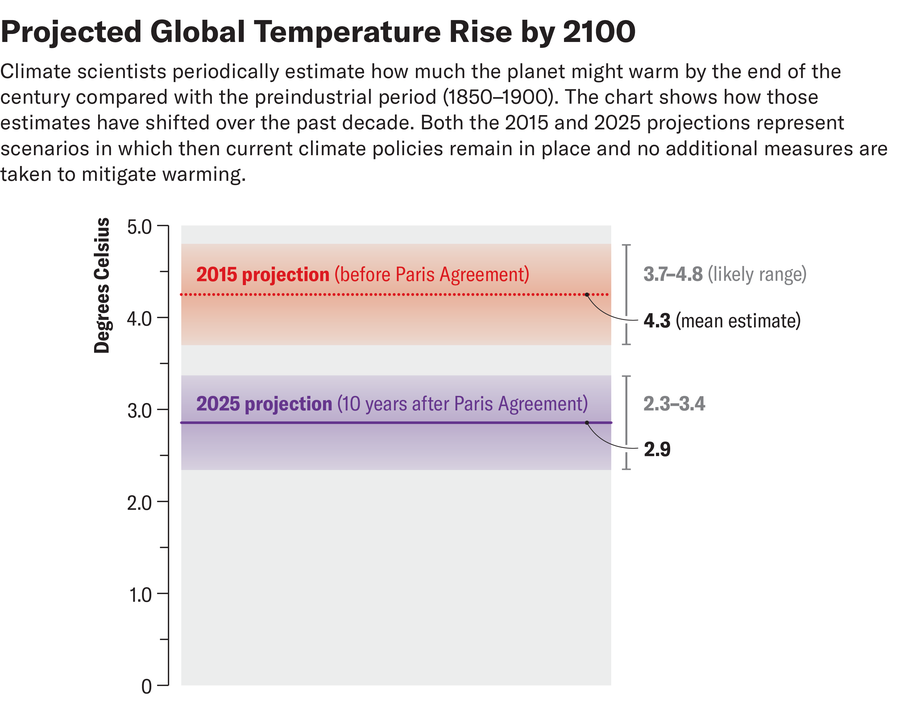

In fact, before the Paris Agreement, the world was expected to see 3.7 to 4.8 degrees Celsius of warming by 2100. But if countries meet their Paris emissions reduction commitments, that level of warming would drop to about 2.9 degrees Celsius, with a likely range of 2.3 to 3.4 degrees Celsius, according to one recent estimate.

However, even under the Paris Roadmap this is still a tall order and its targets allow for some release of carbon pollution into the atmosphere.

“Until global emissions reach net zero,” Samaras says, “the climate impacts of tomorrow will be worse than today.”

Amanda Montanez; Source: Ten Years of the Paris Agreement: The Present and Future of Extreme Heat, Climate Central and World Weather Attribution (data).

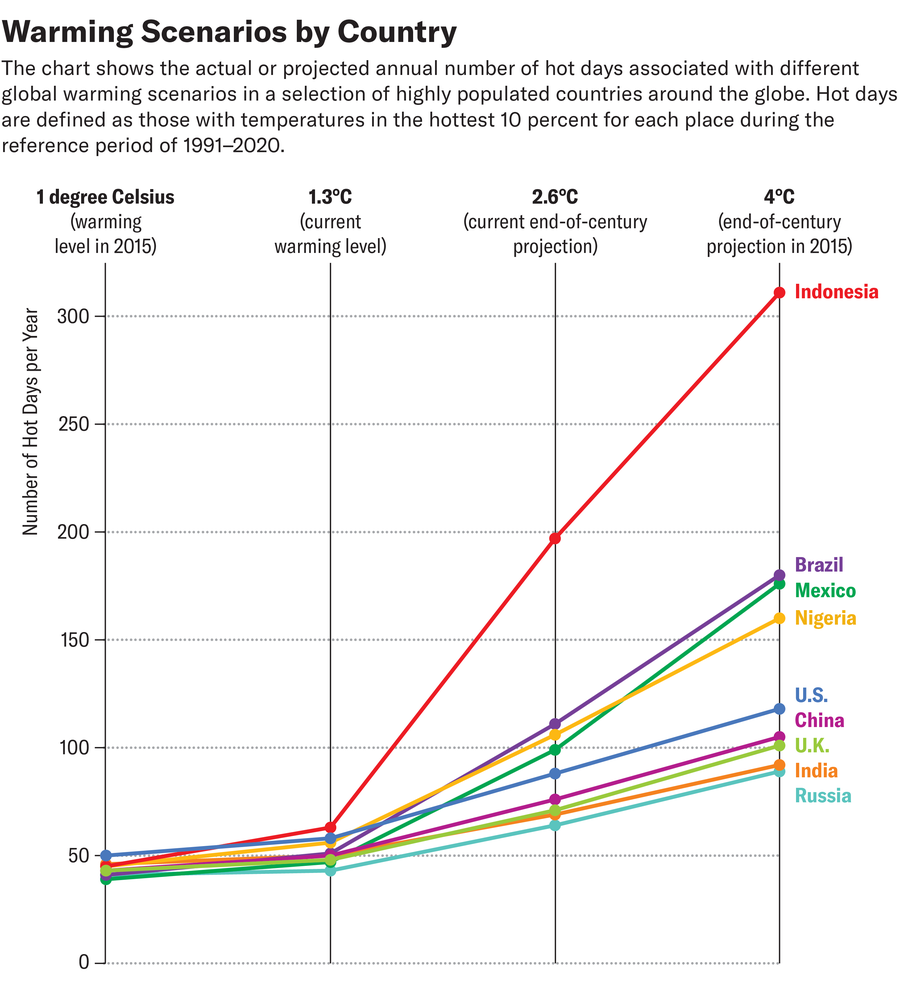

These climate consequences could be dire, although not as dire as those that would have occurred on our pre-Paris path. New research shows that with warming of about four degrees Celsius, US residents face about 118 more extremely hot days than would have happened in a pre-industrial climate by the end of the century. (Other countries would have it even worse.)

If we meet current emissions reduction commitments, the number of heatwave days in the US in 2100 would drop to 88. If we can limit global warming to 1.3 degrees C, the US would only have 58 heatwave days per year on average.

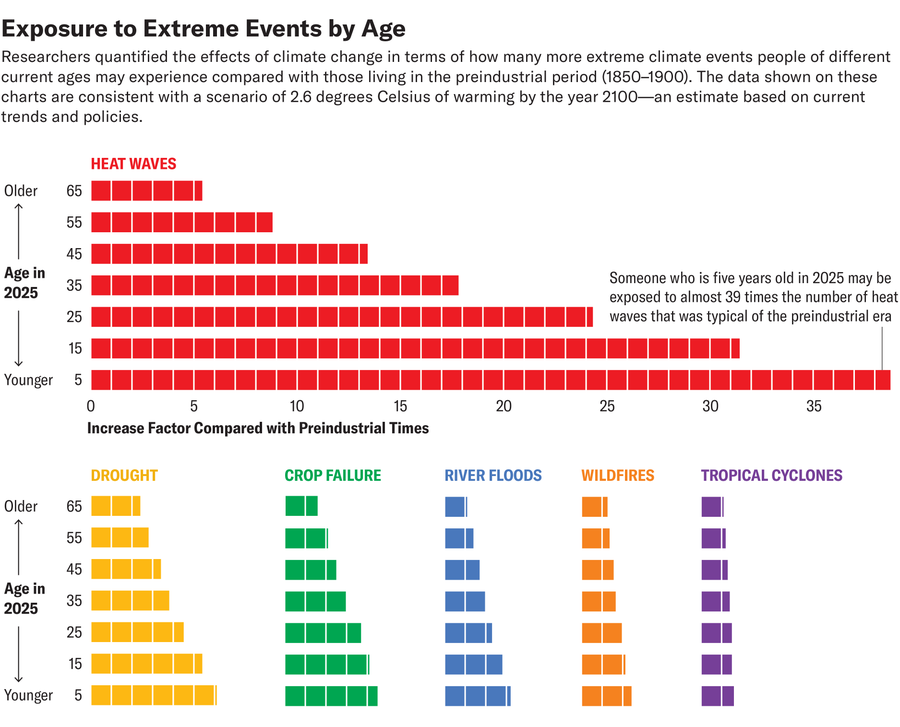

Of course, even if we meet current commitments, there will still be climate impacts. With a warming of 2.6 degrees Celsius. Today's five-year-olds will experience 22 percent more heat waves than today's 15-year-olds, as the work of climate scientist Wim Thierry of Brussels' Frieux University shows. Likewise, today's children will experience more than twice as many heat waves as their 35-year-old parents and more than six times as many as their 65-year-old grandparents.

The frequency of other disasters caused by climate change, including droughts, wildfires and tropical cyclones, is also increasing.

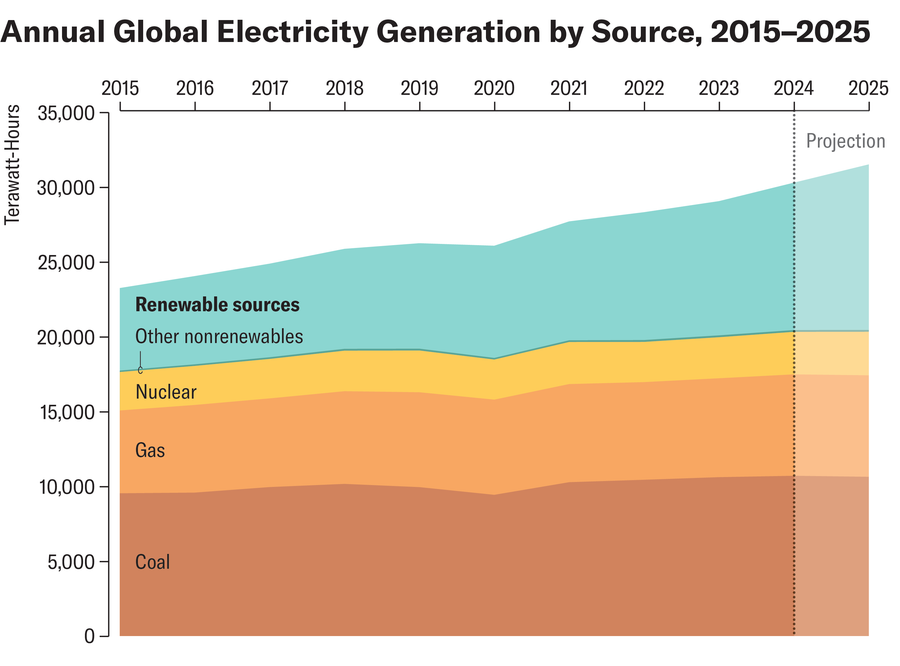

One of the key highlights since the signing of the Paris Agreement is renewable energy surge. A particular achievement is that in 2015 solar energy facilities will be commissioned much faster than anyone expected. Moreover, the energy from these facilities is stored for use at night thanks to battery technology that did not exist when the Paris Agreement was signed. “Batteries are truly a miracle,” says Samaras.

We now need a similar miracle story for sectors such as transport, agriculture, industry and land use. “I hope we can come back to this issue in 10 years and say that the Paris Agreement started a rapid reduction in greenhouse gas emissions,” Samaras says. “But we need to work for the next 10 years to make it happen.”

It's time to stand up for science

If you liked this article, I would like to ask for your support. Scientific American has been a champion of science and industry for 180 years, and now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I was Scientific American I have been a subscriber since I was 12, and it has helped shape my view of the world. science always educates and delights me, instills a sense of awe in front of our vast and beautiful universe. I hope it does the same for you.

If you subscribe to Scientific Americanyou help ensure our coverage focuses on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on decisions that threaten laboratories across the US; and that we support both aspiring and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return you receive important news, fascinating podcastsbrilliant infographics, newsletters you can't missvideos worth watching challenging gamesand the world's best scientific articles and reporting. You can even give someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you will support us in this mission.