November 20, 2025

The Trump administration is making employers feel like they can ignore their legal obligations and trample on workers' rights.

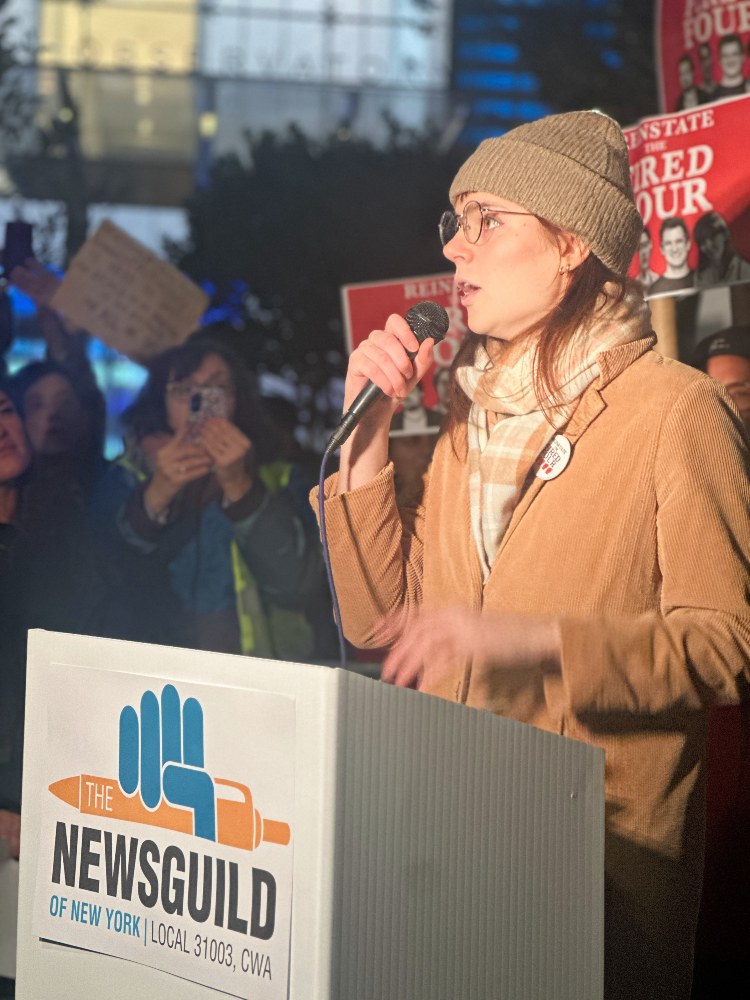

New York City Council member Chi Osse speaks at a rally in support of the Fired Four in front of the Condé Nast offices in New York City on November 12, 2025.

(Courtesy of Condé Nast Union)

Condé Nast illegally fired me from Enjoy your food for raising questions to the HR manager. On November 5th, I participated in our union's attempt to get answers about the layoffs. Two days earlier, Condé announced almost shutters Teenage fashionwhich resulted in the dismissal of eight people. My firing and the firing of three of my co-workers was clearly retaliatory, and if Condé can get away with it (and with President Donald Trump sabotaging the National Labor Relations Board, the company appears to be banking on that), it will send a message to unions and employers in our industry that the foundations of labor law are crumbling.

Since 1935, US law has provided workers with a clear set of rights. The National Labor Relations Act, the legal backbone of the US labor movement, guarantees workers the right to organize unions and demonstrate in the workplace without retaliation from their bosses. The law also created the National Labor Relations Board to enforce labor laws and hold employers and unions accountable for fulfilling their obligations under the law.

Just eight days after taking office, President Donald Trump illegally fired Gwynne Wilcox, the head of the labor council. As a result, the board was left without the quorum required by law to hold meetings and deliberations, limiting the agency's ability to enforce the law.

My union, the NewsGuild of New York, which represents Condé Nast employees, and New York TimesReuters and Nationstruggles with cessation. But the Trump administration and its anti-labor allies know that enforcement of labor laws has eroded and that even under Democratic presidents, NLRB penalties are often not strong enough to dissuade bosses from abusive practices. This emboldens employers to ignore their legal obligations and trample on workers' rights. By firing me and my fellow organizers, my former employer, a supposed beacon of the “liberal media,” seems all too happy to join the GOP in trampling on workers' rights.

We still don't know why the company decided to fire us, but we have theories. Although Conde would certainly say that our attack was not deliberate, it is definitely comfortable given the current political climate. As Vice President of the NewsGuild and a former member of our bargaining committee, I recognize that I am a high-profile target within our union. I was also one of the depressingly few trans women on the staff of any national publication (fired in Teenage fashion also hit Lex McMenamin, the publication's only transgender or non-binary employee), a fact that is especially troubling given the right-wing push to erase trans people from public life and my history criticize a company's track record with your trans employees. Ben Dewey and Jasper Lo, the other two employees fired, both held positions at Condé Nast and New Yorker trade unions accordingly. Wired Reporter Jake Lahut expressed concern about the future of adversarial journalism at Condé. He covered the White House and collected major scoops about The role of DOGE and Elon Musk in the Trump administration. He too was fired, raising further concerns about the kind of journalism Condé is willing to support.

In our case, we are talking about two important protections for workers. The first is the guarantee under Section 7 of the National Labor Relations Act, which guarantees workers the right to self-organize and engage in “concerted activity” in the workplace—essentially, to participate in labor events and demonstrations as long as workers act together as a union. The second is the “just cause” protection in my union contract, which ensures that employees cannot be fired without probable cause and substantial evidence of wrongdoing. This is in contrast to “at-will” employees, who can be fired for almost any reason or for no reason at all. Workers in New Yorker won “just cause” protections in their 2021 union contract, but they weren't extended to the rest of the company until the Condé Nast union threatened to disrupt the Met Gala and won our contract in 2024. “Just cause” is the basis of NewsGuild contracts, and it was intended to protect me from the unfair retaliation I faced when our union tried to get answers from company management.

My last day in Enjoy your food I felt like many other days in my nearly five years working at a food magazine. I arrived at the office Wednesday morning ready to try out the coffee maker I was reviewing. Before heading into the food magazine's famous test kitchen, I completed a few administrative tasks. Our nutrition director and I sampled several cups I brewed with the device I was testing—one was tasteless, another was bitter, and one was more promising—and agreed to do more testing the next day with fresher coffee beans. I washed the dishes and he offered me a plate of pasta, which I quickly ate before heading to a union meeting in the company cafeteria during my lunch break.

In the years since Condé Nast employees joined the union, I've attended countless cafeteria meetings. For me, they are as ordinary things as a Rolex photo shoot. GQ. We discussed the second round of layoffs the company announced this week. Teenage fashion there was special interest. The layoffs wiped out the brand's political department, which was already down to half its size before the company was restructured. Teenage fashionRussia's political vertical covered such issues as youth bans on gender-affirming careyoung climate advocates such as Movement Sunriseand, ironically, looking back, labor organization.

Less than a week before layoffs in Teenage fashionManagement told our union's diversity committee that they were trying to avoid attention from the Trump administration. Coupled with this is the overall media shift to the right to appease the Trump administration (see Stephen Colbert's cancellation, Jimmy Kimmel's near-cancellation, and CBS's takeover of Bari Weiss and Free press) got our union members thinking about the future of journalism at Condé Nast. As good organizers, we channeled these concerns into questions and prepared to take these questions to Stan Duncan, the head of HR.

In union organizing, we call this a “march against the boss,” in which a group of workers approaches the manager, asks a few questions, and then disperses. Sometimes marching officers deliver a letter or petition, often they are met behind a closed door and leave their questions to an assistant, and sometimes they find a superior and receive the information they seek. Marches are a common way for unions to obtain information when managers are not entirely transparent. Condé Union members tried several times this year to meet with Duncan more formally, both at town halls and at committee meetings, but he never attended. So, like many times before, we went to management seeking clarity about our working conditions, job security, and the direction of the company.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

When we arrived, after a short conversation with two HR employees, Duncan walked out of the office and into the hallway to address us. The conversation that followed was routine and boring, especially compared to past marches — a similar demonstration under the Biden administration was nearly double the size on Nov. 5 and ended with a crowd of nearly 50 people booing Duncan over a previous round of proposed layoffs. At that time, not a single employee was threatened with disciplinary action. These demonstrations, perhaps to the chagrin of management, have become the norm for the company since the formation of our union in 2022 and are clearly protected by law and the union contract that the company signed in 2024.

That night I returned to my apartment in Brooklyn after happy hour with friends around 8. evening. Then, while picking out clothes for going to the office the next day before spending the night at my partner's house, I received word from a union representative that Condé Nast was trying to fire me and three of my union colleagues. At 10 eveningI received an email from the company confirming the news: I was being fired for “gross misconduct and violations of policy.”

I was not told what policy I violated or what conduct specifically led to my termination, which is a requirement of my just cause defense. Management did not ask me or my colleagues for our side of the story until the union grievance meeting nine days later. after I was fired. This is the exact opposite of our just cause principles, which ensure that we conduct a thorough investigation before disciplinary action is taken.

Meanwhile, our cause has received overwhelming support from the labor movement, politicians and the legal establishment. A public petition Almost 4,400 signatures have been collected in our support. The Screen Actors Guild, which represents many of the celebrities featured on Condé Nast magazine covers, as well as the Writers Guild and several other unions demanded that I and three co-workers be reinstated. New York City Councilman Chi Osse, who filed papers to challenge House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries in next year's primary and was once presented in GQdid the same at a rally outside the Condé Nast office on November 12. At the same rally, New York Attorney General Letitia James ended her speech with a promise and a threat to my former employer: “Condé Nast, I’ll see you in court.”

Our union does not stand idly by. Through rallies, training programs, and other demonstrations of our growing power within the office, we're putting pressure on Condé Nast to do the right thing, and our support is only growing. Our petition is still active – you can sign up for updates at how to support our campaign from outside – and we have already raised almost $15,000 for support the fired four while we are fighting back against the company. Condé Nast can correct this mistake and reinstate us at any time, but like the Trump administration itself, the company's leadership seems to believe that bosses are not subject to questioning.