Faisal IslamEconomics editor

BBC

BBCGoogle's ultra-private CEO Sundar Pichai is showing me around Googleplex, its California headquarters. A walkway runs along the length of it, passing by a giant dinosaur skeleton, a beach volleyball pitch and dozens of Googlers lunching under the hazy November sun.

But it's a laboratory, hidden away at the back of the campus behind some trees, that he is most excited to show me.

This is where the invention that Google believes is its secret weapon is being developed.

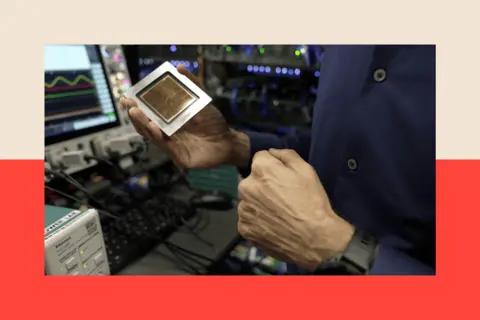

Known as a Tensor Processing Unit (or TPU), it looks like an unassuming little chip but, says Mr Pichai, it will one day power every AI query that goes through Google. This makes it potentially one of the most important objects in the world economy right now.

“AI is the most profound technology humanity [has ever worked] on,” he insists. “It has potential for extraordinary benefits – we will have to work through societal disruptions.”

But the confusing question lingering over the AI hype is whether it is a bubble at risk of bursting – as, if so, it may well be a spectacular burst akin to the dotcom crash at the start of the century, with consequences for us all.

Bloomberg via Getty Images

Bloomberg via Getty ImagesThe Bank of England has already warned of a “sudden correction” in global financial markets, saying “market valuations appear stretched” for tech AI firms. Meanwhile. OpenAI boss Sam Altman has speculated that “there are many parts of AI that I think are kind of bubbly right now”.

Asked whether Google would be immune from a potential bubble burst, Mr Pichai said it could weather that potential storm – but for all his starry-eyed excitement around the possibilities of AI, he also issued a warning: “I think no company is going to be immune, including us.”

So why, then, is Google investing more than $90bn a year in the AI build-out, a three-fold increase in just four years, at the very moment these suggestions are being discussed?

The big AI surge – and the big risk

The AI surge – of which Google is just one part – is, in cash terms, the biggest market boom the world has seen.

Its numbers are extraordinary – there is $15 trillion of market value at Google and four other tech giants whose headquarters are all within a short drive of one another.

Chipmaker turned AI systems pioneer Nvidia in Santa Clara is now worth more than $5 trillion. A 10-minute drive south, in Cupertino, is Apple HQ, hovering around $4 trillion; while 15 minutes west is $1.9 trillion Meta (previously Facebook). And in the centre of San Francisco, OpenAI was recently valued at $500bn.

The purely financial consequences of this trend are significant enough.

The value of the shares in these companies (and a few others outside Silicon Valley, such as Microsoft in Seattle) have helped cushion the US economy from the impact of trade wars, and kept retirement plans and investments buoyant – and not just in the US.

Yet it comes with a big risk. That is, the incredible dependence of US stock market growth on the performance of a handful of tech giants. The Magnificent 7 – Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia, and Tesla – collectively comprise one third of the valuation of America's entire S&P 500.

And that market value is now more highly concentrated in a few firms than it was during the dotcom bubble in 1999, according to the IMF.

Mr Pichai points out that every decade or so come these “inflection points”: the personal computer, then the internet in the late 1990s, followed by mobile and cloud. “Now it's clearly the era of Artificial Intelligence.”

But as for the big question – is it a bubble?

Mr Pichai argues there are two ways of thinking about it. First, there is “palpably exciting” progress of services that people and companies are using.

But he concedes: “It's also true when we go through these investment cycles, there are moments we overshoot collectively as an industry…

“So I think it's both rational and there are elements of irrationality through a moment like this.”

Now, a distinction is emerging in the markets between those businesses that rely on often borrowed money and complicated deals to access the chips that power their AI, and the biggest tech companies, such as Google, Microsoft and Amazon, which can fund investment in chips and data from their own pockets.

Which brings us to Google's own silicon chips, or their prized TPUs.

‘Restricted': inside the silicon chip lab

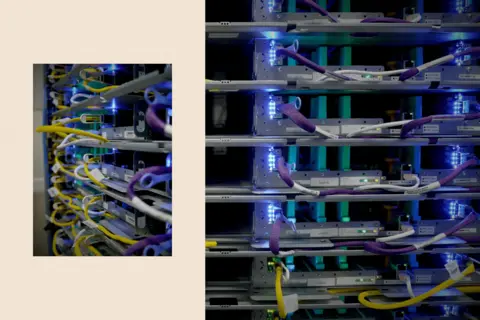

The lab, where they are tested, is the size of a five-a-side football pitch with a mesh of multi-coloured wires and deep blue blinking lights. Signs all around read: “restricted”.

What's striking is the sheer noise – this is down to the cooling systems, which are needed to help control the temperature of the chips, which can get incredibly hot when crunching trillions of calculations.

The TPUs are designed to help power AI machines. And they work differently from other types of chips.

The CPU (central processing unit) is the primary component of a computer – essentially its brain – that performs most of the processing and control functions, while GPUs (graphics processing units) perform more specialised processing, executing many parallel tasks at once – this can include AI.

However Asics (application-specific integrated circuits), are chips custom-built for a specific purpose, for example, a specific AI algorithm. And the TPU is a specialist Google-designed type of Asic.

A core aspect of the AI boom has been the mad dash to amass lots of top-performing chips and put them into data centres (or the physical facilities that store, process and run large amounts of data and software).

Nvidia's boss Jensen Huang once coined the term “AI factories” to describe the massive data centres full of pods and racks of super chips, connected to huge energy and cooling systems.

(Tech bosses such as Mark Zuckerberg have referred to some being the size of Manhattan. The Google TPU lab is somewhat more modest, testing out the technology for deployment elsewhere.)

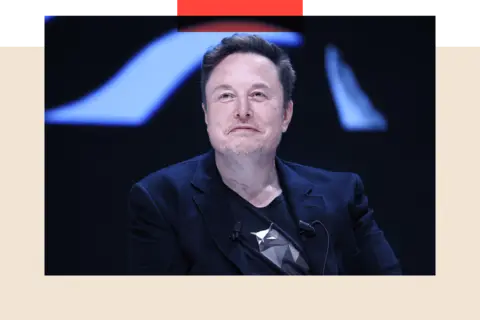

Stories abound of tech bros begging chip makers for hundreds of thousands of these highly engineered pieces of silicon. Take the recent dinner at Nobu in Palo Alto, where Elon Musk and Larry Ellison, the founder and head of Oracle, tried to woo Nvidia's Jensen Huang, to sell them more of them.

As Mr Ellison put it: “I would describe the dinner as me and Elon begging Jensen for GPUs. Please take our money – no, no take more. You're not taking enough. We need you to take more, please!”

It is precisely the race to access the power of as many as possible of these high performance chips, and to scale them up into massive data centres, that is driving an AI boom – and there's a perception that the only way to win is to keep spending.

The chips race – and the OpenAI storm

The terrace of the Rosewood Sand Hill hotel, a sprawling 16-acre estate near the Santa Cruz mountains that serves crab rolls and $35 signature vodka martinis, is where the big Silicon Valley deal-making gets done. It's close to Stanford University and Meta's HQ, as well as the headquarters of major venture capital firms.

There are whispered rumours about who will be next to announce customised AI chips – Asics – to compete with Google and Nvidia.

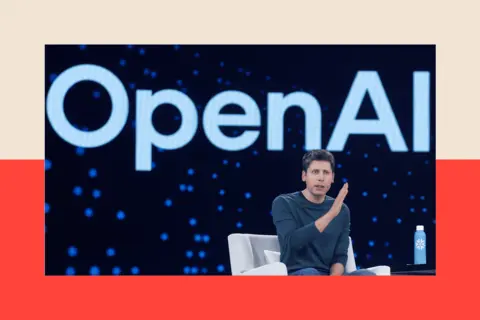

Just before I visited, something of a storm was brewing about the investment plans of OpenAI, which Elon Musk co-founded.

The firm, which started as a not-for-profit but has since established a commercial structure, has been the focus of a web of cross-investments involving buying up chips and other computer hardware needed for AI processing.

Few in the industry doubt OpenAI's phenomenal user growth – in particular the popularity of its chatbot, ChatGPT. It has ambitions to design its own custom AI chips, but some have speculated about whether it might need government support to achieve this.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn a podcast episode that aired last month, an OpenAI investor questioned how the company's spending commitments tallied with its revenues, to which co-founder Sam Altman shot back, challenging the revenue figures quoted, and adding: “If you want to sell your shares, I'll find you a buyer. Enough.”

He has since shared a lengthy post on X, explaining, among other things, that OpenAI is looking at commitments of about $1.4 trillion over the next eight years and why he believes now is the time to invest in scaling up their technology.

“I do not think the government should be writing insurance policies for AI companies,” he said.

But he also said: “What we do think might make sense is governments building (and owning) their own AI infrastructure.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesElsewhere, there have been notable very recent falls in share prices of AI infrastructure companies – Coreweave, a start-up that supplies OpenAI, saw its shares lose 26% of their value earlier this month.

Plus, there have been some reactions in markets for perceived credit risk among other firms. And while most of these tech share prices have generally climbed higher over the course of 2025, there has been a mild dip more generally in the past few days.

ChatGPT versus Gemini 3.0

None of this has dampened the excitement over AI's potential within the industry. Google's consumer AI model, Gemini 3.0, launched to great fanfare earlier this week — this will pitch Google in a direct battle with OpenAI and its still-dominant ChatGPT for the market share.

What we don't yet know is whether it marks an end to the days of chatbots going rogue and recommending glue as a pizza ingredient. So, is the end result of all this fantastic investment is that information is less reliable, I asked Mr Pichai.

“I think if you only construct systems standalone and you only rely on that, [that] would be true,” he told me. “Which is why I think we have to make the information ecosystem has to be much richer than just having AI technology being the sole product in it.”

But I put it to him that truth matters. His response: “truth matters”.

Nor is the other big question facing tech today dampening the enthusiasm around advancing AI's potential. That is: how on Earth to power it?

By 2030, data centres around the world will use about as much electricity as India did in 2023, according to the IMF. Yet this is also an age where energy supply is under pressure by governments committing to climate change targets.

I put this to Google's Mr Pichai, asking if it is coherent to have ambitions to generate 95% of electricity from low-carbon sources by 2030 – as the UK government does – and also be an AI superpower?

“I think it's possible. But I think for every government, including the UK, it's important to figure out how to scale up infrastructure, including energy infrastructure.

“You don't want to constrain an economy based on energy,” he adds. “I think that will have consequences.”

Lessons from the 2000 dotcom bust

Years ago, as a fledgling reporter I cut my teeth in the 2000 dotcom bubble. It followed a famous speech by Federal Reserve Governor Alan Greenspan about “irrational exuberance”.

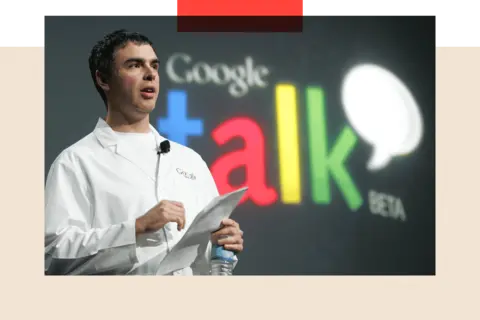

In that time I interviewed Steve Jobs twice, and a few years later questioned Mr Pichai's predecessor Larry Page, and commentated live on the collapse of WorldOfFruit.com.

Through it all, one lesson became clear: that even in the worst-case scenarios and the toughest of crashes, catastrophe isn't guaranteed for all.

Take Amazon – its share price slumped to $6 and its market capitalisation fell to $4bn during that crash, yet some 25 years on Jeff Bezos and his company are very much going strong. Today Amazon is worth $2.4 trillion.

The same would, inevitably, be true of companies shaken by a potential AI bubble burst.

WireImage

WireImagePlus there is another looming factor that may well explain why so many in Silicon Valley – and beyond – are blind to, or perhaps choosing not to, acknowledge this risk, and pushing on regardless.

That is, the attraction of the glittering prize at the end: achieving artificial general intelligence (AGI).

This is the point at which machines match human intelligence, something many believe is within reach. Or beyond that, reaching artificial super-intelligence (ASI), the point at which machines surpass our intelligence.

But I was also told something else that was thought-provoking by a Silicon Valley figure – that it doesn't matter whether there really is a bubble or if it bursts. Step back and what is going on in the bigger picture is a global battle for AI supremacy, with the US against China taking centre stage.

And while Beijing funds these developments centrally, in the US it is a messy but productive free market free for all, which means trial and error on an epic scale.

For now, the US has superiority in silicon over China – companies like Nvidia with their GPUs and Google with their TPUs can afford to accelerate into the storm.

Others will surely fail, and spectacularly so, affecting markets, consumer sentiment and the world economy. The physical footprint left behind, however, containing sheer computing firepower for the deployment of mass AI technologies, will inevitably shape our economy and could well also shape how we work and learn – and who dominates the world for the rest of the 21st Century.

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. You can now sign up for notifications that will alert you whenever an InDepth story is published – click here to find out how.