Rita Orr, 94, and her daughter Janice Rogers sit across from each other at a small table playing Bingo.

Ashley Milne-Tite

hide signature

switch signature

Ashley Milne-Tite

Several years ago, Janice Rogers of Belchertown, Massachusetts, made a decision that many adult children dread. Her mother, Rita, was 91 at the time, living alone in her mobile home and in declining health.

“I didn’t feel like I could take care of my mom, and that’s terrible,” Rogers says. “I felt like I needed to ‘put’ her somewhere.”

Since then, her mother, now 94, has developed dementia. But Rogers' first choice didn't work out. Where her mom now lives is known as a continuing care retirement community, or CCRC, called Loomis Lakeside in Reed's Landing in Springfield, Massachusetts. CCRCs offer several levels of care, from independent living to assisted living, memory care and skilled nursing facilities. According to Lisa McCracken, the company's head of research and analytics. network card – National Investment Center for Seniors Housing and Care – The number of memory care units in the United States has grown 62% over the past decade. But this community is unusual: it does not have a memory care unit. It is part of a movement to make the lives of people with dementia less isolated and more integrated.

Freedom and inclusion

Rita Orr, Rogers' mother, currently lives in the skilled nursing facility. She can walk around the facility as much as she wants, including going outside. What's good about her daughter.

“She sees freedom, but she's okay with it,” Rogers says. “Having a locked door? She wouldn't like it.”

Laurie Todd, executive director of Loomis Lakeside in Reed's Landing, said people sometimes try to leave locked memory care units precisely because they feel trapped. Here, she said, they want people with dementia to live as well as possible in the community.

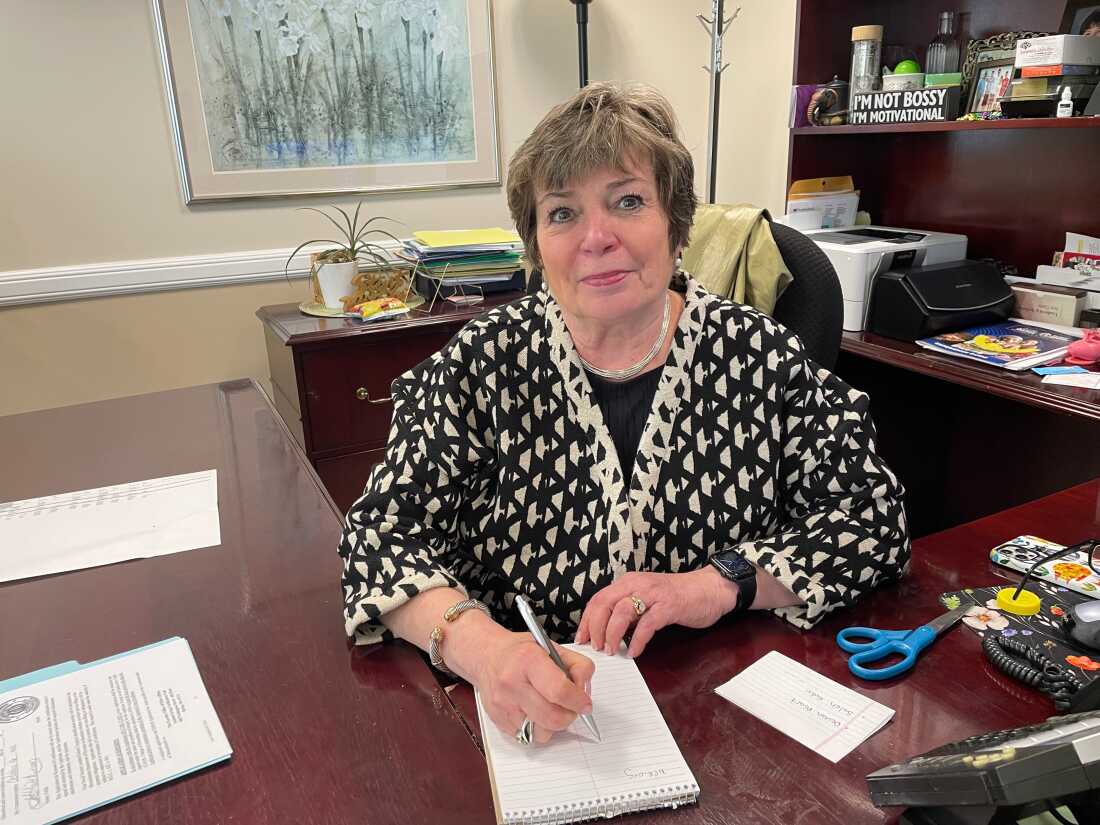

Laurie Todd, executive director of Loomis Lakeside in Reed's Landing, says including people with dementia in the broader community is “a much more dignified way of caring for people.”

Ashley Milne-Tite

hide signature

switch signature

Ashley Milne-Tite

“What we do is meet them where they are and work with other residents to teach them how to be good neighbors” for those living with dementia, Todd says. “So we don't isolate them, just like we don't isolate people who all had congestive heart failure or diabetes.”

Staff and resident training

Todd says they train staff and residents on how to interact with people with dementia, such as how to talk to someone who is looking for a deceased spouse or how to calm someone down if they are upset. This often involves redirecting them or including them in a new activity. She says staff closely monitor dementia patients to decide whether they can go out unaccompanied or whether they need an aide to accompany them.

If this approach to treating dementia sounds unusual, that's because it is. Todd says it's a small but growing movement. “It's really taking off,” she says. “It’s a much more dignified way to take care of people.”

Both residents and staff are involved in this process. Ann McIntosh has lived here for 16 years and is grateful for the dementia education she received. The key to connecting with a neighbor with dementia is to meet the person in their world, rather than bringing them back to the present, she says.

“When someone wants to visit their husband, who I know died five years ago, I say, 'Yeah, let's see what we can find,'” McIntosh says. Then, as they walk down the hallway, she says, the person with dementia may notice a group of people and want to join them. “So that solved the problem because they don't remember where they started,” she says. “And just being able to involve them in the process makes me feel better because we’re all part of the same community.”

Neighbor Helen Houston agrees, saying the dementia education program has “made it seem like dementia isn't such a big deal for people.” It also made her feel really good about the place she calls home.

Loomis Lakeside at Reed's Landing Helen and Whiting Houston residents volunteer some of their time working with residents living with dementia.

Ashley Milne-Tite

hide signature

switch signature

Ashley Milne-Tite

She and her husband volunteer their time at program for fellow villagers with dementia called Saido trainingoriginated in Japan. “We do brain exercises with them,” Houston says, “exercises that involve both math and English. They are happy when they see a person's cognitive abilities improve as a result of regular class attendance.

“Behavior is an unmet need”

Brenda Mendoza is the Director of Enhanced Living and Memory Care. Staff training is mandatory, she said. This is voluntary for residents. And many residents have questions about this way of doing things. Mendoza says she often meets with them one-on-one “and talks a little bit about why we're doing this and what's the benefit of it? And how would you feel?

Brenda Mendoza, director of enhanced living and memory care at Loomis Lakeside in Reed's Landing, trains staff and residents on how to communicate with residents living with dementia.

Ashley Milne-Tite

hide signature

switch signature

Ashley Milne-Tite

Mendoza says that when it comes to managing behaviors such as aggression or agitation, which are often associated with dementia, “behavior is an unmet need.” She says she and staff are working hard to figure out what's causing the behavior. Is the person scared, hungry, in pain, or missing his family?

“Just a question: How do we figure out what they like or enjoy doing? Let me try to get them involved in what they were doing before,” she says.

But the thought of not having an enclosed memory care unit is off-putting to those concerned about safety. Arnie Beresh is a former orthopedic surgeon who was diagnosed with dementia at age 62. “I describe it as hitting a wall at about 200 miles an hour,” he says.

This was 10 years ago. Beresh tried to slow the progression of the disease by eating well, exercising and staying socially active. He says his brain works best in the morning, but by lunchtime, “I run out of gas.”

He lives at home with his wife in Michigan, but knows he might live elsewhere at some point. “I believe in memory blocking,” he says. “And my reason is that I think it's more of a safety factor for the patient with dementia.”

Autonomy and change of ideas

Many family members of people with dementia agree and believe that a locked door is the best way to ensure their loved ones do not leave the facility and put themselves in danger. Kirsten Jacobs understands this. She works for Leading Age, a network of organizations serving older adults.

“I think it's really important to acknowledge that instinct of wanting to protect our loved ones,” she says. “But what do we lose… when we focus exclusively on one type of security, without recognizing the richness that a life that allows for some freedom, flexibility and autonomy can provide?”

Jacobs says if you go back a few decades to common practice in nursing homes, “we used to tie people up, and it was in the name of safety. We realized that this was not the safest approach, and this is no longer the model we follow.”

She points to a movement that began in the late 1980s called “Unleash the Seniors.” discourage the use of restraints in nursing homes and other medical institutions.

She adds that there is another practical reason for a more inclusive approach to dementia care. “We can't build enough bricks and mortar…individual memory care communities to meet the needs of people living with dementia,” she says. “So we have to think more broadly.”

“They treated me like a person”

Joanna Fix, a longtime psychology professor, was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease when she was in her 40s. Now 57, she is adamantly opposed to closed memory care units.

“One of the problems I see is that the people who make decisions about memory care are family members,” she says, while she is the one living with the condition. She would like more people to learn about what it means to have this disease and act accordingly.

“People with healthy brains decide how they want to interact with those of us living with dementia,” she says.

Arnie Beresh and his cat Coner. Beresh has been living with dementia for 10 years.

Beresh family

hide signature

switch signature

Beresh family

Arnie Beresh feels the same way. He says no matter where people with dementia live, “the main thing is we still need to be treated as individuals.”

Because, according to him, even if the disease is advanced, the person is still there.