Siona McCallumSenior Technology Reporter

BBC

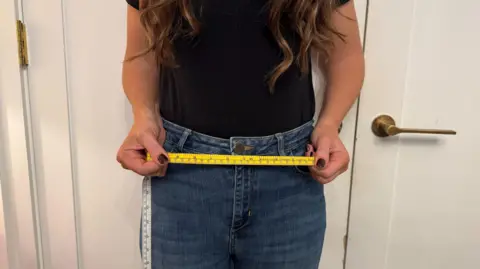

BBCMost women are familiar with the pain of being mismatched in sizes at big box stores.

A pair of jeans can easily be a size 10 from one brand and a size 14 from another, leaving shoppers confused and frustrated.

This has led to a global flood of returns, costing fashion retailers an estimated £190 billion a year as potential shoppers wonder what size and which store they should buy from.

I didn't have to look far to find people experiencing this problem.

“I don’t trust fashion sizes,” one woman tells me as she walks along one of London’s popular shopping streets. “To be honest, I buy based on how it looks rather than the actual size.”

She's one of many women who often order multiple versions of the same item to find the one that fits before sending the rest back, fueling a culture of mass returns.

New generation of calibration technology

A growing cluster of tech companies is now trying to solve this problem.

Tools such as 3DLook, True Fit and EasySize help shoppers choose the right size at checkout, using body scans via smartphone photos to offer the most accurate fit.

Meanwhile, virtual fitting room platforms, including Google Virtual Try-on, Doji, Alta, Novus, DRESSX Agent and WEARFITS, allow shoppers to create digital avatars and preview how items might look. These systems are designed to increase confidence when purchasing online.

More recently, sales agents powered by artificial intelligence have also begun to enter the market. Daydream allows users to describe what they are looking for and then recommends options.

OneOff collects celebrity images to find similar products, while Phia scans tens of thousands of websites to compare prices and get early “size information.”

While these tools work at the e-commerce stage, new UK startup Fit Collective is taking a different approach: trying to prevent the problem earlier in the production process.

Company founder Phoebe Gormley says artificial intelligence could potentially correct sizing before clothes reach stores.

The 31-year-old, who is not a data scientist but rather a tailor, previously launched Savile Row's first women's tailor, making bespoke clothes for a wide range of women.

“They all came in and said, 'Regular sizes are so bad,'” she tells me.

She says the current fashion model is a “downward spiral” where brands make cheaper clothes to offset huge return rates, leading to dissatisfied customers and more waste.

Since launching last year, Fit Collective has raised £3 million in pre-seed funding, reportedly the largest amount ever raised by a single female founder in the UK.

“To our knowledge, we are the first solution that compares all production and commercial data,” she says.

Phoebe's new venture uses machine learning to analyze a range of data, including returns, sales figures and customer emails, to really understand why something isn't a good fit.

This then turns into clear guidelines for design and production teams, who can adjust designs, sizes and materials before production begins.

Her system might, for example, suggest that a firm reduce the length of an item of clothing by a few centimeters to reduce the overall number of returns. This saves the company money and the consumer time.

While many in the industry welcome such tools, some warn that technology alone will not solve fashion's sizing problem.

“People are not mannequins, they are unique, and so are their body shape preferences,” says Paul Alger, director of international business at the British Fashion and Textile Association.

He warns that sizing can be nuanced: body measurements rarely match the numbers on the label.

“It’s very difficult, it’s very subjective,” he says.

“Most of us are different shapes and sizes—people all over the world have different body shapes.”

And then there's the issue of vanity sizing—or, in Mr. Alger's words, “emotional sizing,” where a brand deliberately chooses a more generous approach knowing that the consumer, especially in women's clothing, will choose to shop there.

“Once these sizing norms are established in a collection, brands will typically look to them each season to effectively create their own signature sizes,” he says.

Sophie De Salis, sustainability policy advisor at the British Retail Consortium, says retailers are becoming increasingly aware of the issue from a cost-saving and sustainability perspective.

“Smart sizing technologies and AI solutions are key to reducing margins and supporting the industry's sustainability goals. BRC members work with innovative technology providers to help their customers buy the right size and reduce profits,” she says.

With profits now a boardroom issue and pressure on sustainability growing, more fashion houses may well consider data-driven design.

While no single solution is likely to completely solve the problem of size mismatch, the emergence of tools like Fit Collective, along with a growing ecosystem of virtual try-ons and size prediction platforms, suggests the industry is beginning to change.