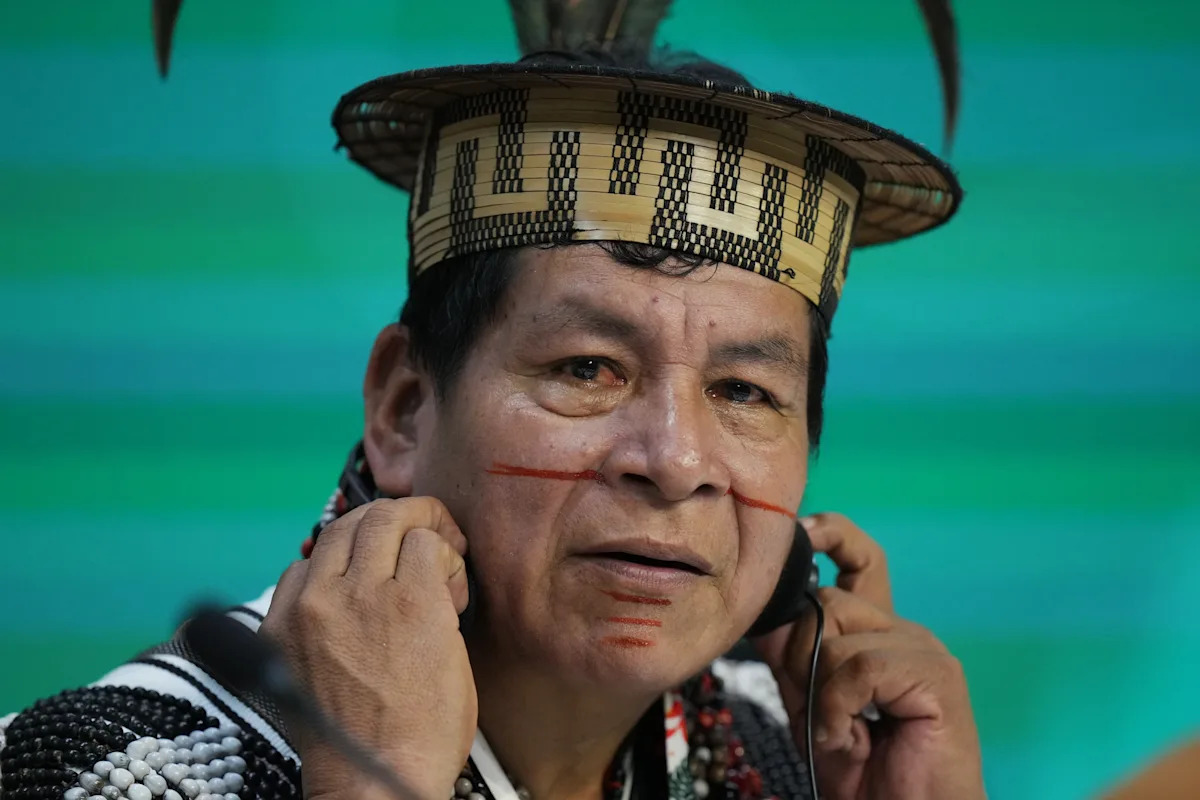

BELEM, Brazil (AP) — Indigenous people are used to adapting, so when authorities failed at this year's kickoff event UN climate talksthey rolled with it. Participants from around the world sweated through songs, dances and prayers, improvising without microphones and cooling off with fans made of paper or leaves.

But the untimely power outage has fueled lingering skepticism that this year's summit, dubbed the “Indigenous COP,” will deliver on organizers' promise to put them at the center of an event on the edge of the Amazon rainforest, where many indigenous groups live.

Indigenous peoples conserve most of the world's biodiversity and are among those who contribute least to climate change, but are also disproportionately affected by the devastation it causes.

“We are working within a mechanism and we are working within an institution that we know was not created for us,” said Talia Yarina Cachimuel, a member of the Kichwa-Otavalo Delegation of the Guardians of Wisdom, a global group of indigenous peoples from around the world. “We’re going to have to work 10 times harder to make sure our voices are part of the space.”

This year's climate talks, which run until November 21, are not expected to result in an ambitious new deal. Instead of, organizers and analysts create it The annual conference as a “COP on implementation”, aimed at fulfilling past promises.

A conference that's hard to get to

climate talks — known as the Conference of the Parties, or COP30 this year — has long left indigenous peoples on the sidelines or sidelined.

Many are underrepresented in governments that have often forcibly colonized their people. Others face language barriers or travel difficulties that prevent them from traveling to conferences such as COP30.

The Brazilian government said holding this year's summit in Belem was partly a tribute to indigenous groups who can live sustainably in the Earth's wild spaces.

But indigenous groups, like other activists, have not traditionally participated in climate talks unless individual members are part of a country's delegation. Brazil has included them on its list and encourages other countries to do the same. It was not immediately clear how many people did so in Belem.

But there's a big difference between visibility and getting into the meat of the negotiations, Cachimuel said.

“Sometimes that's where the gap lies, right? Like, who can participate in high-level dialogues, you know, who are the people who meet with states and governments,” she said.

She was concerned that inclusion efforts would not be continued at future COPs.

Edson Krenak, a representative of the Krenak people and the Brazilian manager of the indigenous rights group Cultural Survival, said he saw less indigenous participation than he expected. He attributed this partly to difficulties finding a place to live. Belem, the small town that fought to quickly expand hosting opportunities at COP30.

He said it was frustrating when Indigenous people were not involved in policy development from the start but were expected to comply with them.

“We want to make these policies, we want to be part of the really fantastic solutions,” Krenak said.

However, the fact that this COP is in the Amazon “makes the indigenous people the host,” said Alana Mancineri, who works with COIAB, an Amazon indigenous organization like herself.

Fighting for voices to be heard

At the opening of the Indigenous Pavilion, the lack of electricity was not the only problem. The presenters did without an official translator.

One of the speakers, Wis-waa-cha from the Coast Salish and Nuu-Cha-Nulth lands, said a lack of attention to such details can make people feel “constantly rejected in a very passive way.”

The Brazilian presidential administration did not immediately respond to questions about why there was no translator at the event. The report said they tried to resolve the power outage as quickly as possible.

World leaders should focus on direct funding for communities that need support, said Lucas Che Ical, who represented Ak'Tenamit, an organization that supports education, climate change and health initiatives in indigenous and rural villages in Guatemala.

He knows that often in past conferences the agreements reached did not have a direct positive impact on the lives of Indigenous peoples. He hopes things will be different this year.

“I’m an optimistic person,” he said, speaking in Spanish. “There is a view that yes, it can produce good results and that governments making decisions can make a positive decision.”

Above all, he said he hoped that decision-makers at this COP “can listen to the voices of indigenous villages, local communities and all the villages of the world where they live in poverty and are part of the effects of climate change.”

___

Follow Melina Walling on X @MelinaWalling and Bluesky @melinawalling.bsky.social.

___

Associated Press climate and environment coverage receives financial support from several private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find hotspots standards for working with charities, list of supporters and funded coverage areas on the website AP.org.