Getty Images

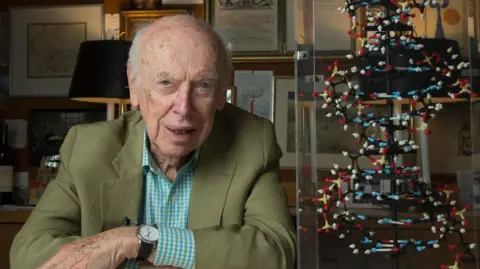

Getty ImagesIn February 1953, two men walked into a pub in Cambridge and claimed to have found “the secret of life.” This was not empty boasting.

One of them was James Watson, an American biologist from the Cavendish Laboratory; the other was his British research partner Francis Crick.

Their discovery of the structure and function of deoxyribonucleic acid or DNA ranks alongside the discoveries of Mendel and Darwin in its significance for modern science.

The full Promethean power of their achievements will gradually become clear over decades of research by fellow geneticists.

It also opened a Pandora's box of controversial scientific and ethical issues, including human cloning, designer babies and Frankenstein food.

Demonstrating that DNA has a three-dimensional double helix shape allowed Watson and Crick to unlock the secrets of how cells work; the means by which characteristics were passed down from generation to generation.

“When we saw the response, we had to pinch ourselves,” Watson said. “We realized it was probably true because it was so beautiful.”

This discovery earned them the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1962 and a permanent place in the historical ranks of the great thinkers of science.

It also ensured that if they said something controversial, it would make headlines.

And Watson had a lot to say, most famously about the connection between race and intelligence.

Gonville and Caius College

Gonville and Caius CollegeWhen he first suggested that black people were less intelligent, London's Science Museum canceled a planned lecture, insisting that Watson's views were “beyond the bounds of acceptable debate.”

He suggested that “when you interview fat people, you feel bad because you know you're not going to hire them.” And he wondered aloud whether beauty could—or should—be genetically encouraged.

Watson has come under fire for saying women should have the right to abort their unborn child if tests confirm he is gay.

He argued that he was simply pro-choice, that it would be equally acceptable to favor homosexual offspring, and that it was simply natural to want grandchildren.

He alienated many in his profession by calling many fellow scientists “dinosaurs”, “slackers”, “fossils” and “has-been” in his autobiography, Avoid Boring People.

In 2014, he became the first living Nobel laureate to auction off his medal, in part to help fund future scientific discoveries. A Russian tycoon bought it for $4.8 million (£3 million) and promptly gave it back to him.

early life

James Dewey Watson was born in Chicago on April 6, 1928, into a family that believed in “books, birds and the Democratic Party.”

He was the only son of Jean and James, descendants of English, Scottish and Irish settlers.

His political interest came from his mother, who worked for the Democrats. During elections, the basement of their bungalow will be used as a polling station.

His father's passions were science and bird watching. Young Watson accompanied his father on bird-watching trips. He learned that science is a discipline that requires careful observation of nature.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThis left no room for faith. Raised as a Roman Catholic by his mother, Watson called himself “a fugitive from that religion.”

“The happiest thing that ever happened to me was that my father didn’t believe in God,” he said.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, his father's salary was suddenly cut in half, and he rushed to the bank to withdraw his remaining savings in time.

Watson slept in a tiny attic room with his younger sister Betty.

He was a skinny teenager who was told to go buy milkshakes to “fat him up.” He was socially awkward and was expelled from school for poor grades – his work was severely affected by a bout of scarlet fever.

“None of my classmates thought I would achieve much,” he recalled.

He did not consider himself a man of precocious intelligence, but received a scholarship to the University of Chicago at the tender age of 15.

He explained this by saying that “my mother knew the dean of admissions.”

Intellectual flourishing

University liberated him from the complex social hierarchy of school life, where popularity and physical development were crucial. This created an environment in which the talented but awkward teenager could thrive.

Watson considered majoring in ornithology, the study of birds, but switched to genetics – influenced by Erwin Schrödinger's What Is Life?

He described the University of Chicago as an “idyllic academic institution” where he was “instilled with the capacity for critical thinking and the ethical commitment to not suffer fools who thwarted his search for truth.”

The prevailing scientific wisdom was that genes are proteins that can reproduce themselves. The presence of DNA was dismissed as something “silly” simply meant to support the protein.

Watson became fascinated by the new technique of diffraction, in which X-rays were reflected from atoms, revealing their internal structure.

He became convinced that DNA had its own structure and was determined to find it. He thought that the place to do this was England.

Scientific photo library

Scientific photo libraryAt Cambridge he met Francis Crick, a physicist by training who had “extraordinary conversational powers” and “the loudest laugh I ever knew.”

They began building large-scale models of possible DNA structures and trying to match them with existing data. In one of the biggest scientific controversies of all time, not all of this evidence was their own.

Watson and Crick competed against another team from King's College London. Their opponents were Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin. They got along well with him and terribly badly with her.

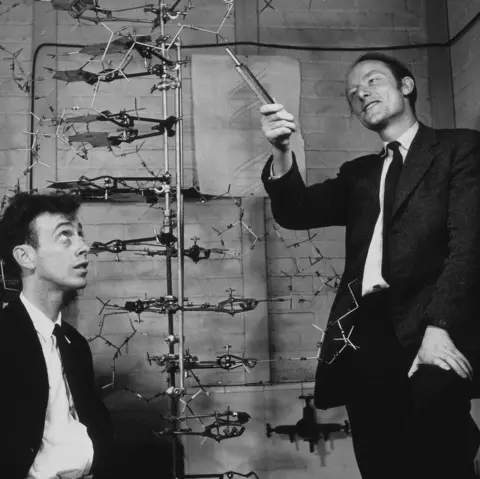

Rosalind Franklin

Wilkins corresponded with the Cambridge couple, sometimes exchanging thoughts and ideas.

But Franklin was different. She was an accomplished chemist and expert in diffraction.

Together with her student Raymond Gosling, she photographed the patterns created by X-rays as they reflected off DNA molecules.

Watson and Crick considered Franklin “hostile” and thought that she jealously guarded her research and worked in isolation.

They made disparaging comments about her appearance, but Watson was not averse to looking at her work when Wilkins suggested.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe key piece of evidence was Photo 51.

It shows a fuzzy X-ray pattern that captivated the Cambridge couple. They threw themselves into building models, testing each theory against new information.

From this they concluded that DNA must have a three-dimensional double helix structure—like a twisted ladder with rungs formed by alternating salt and phosphate groups.

Their key findings were that in the case of splitting, each thread represents a template for creating another and that the order of the “rungs” represents the code.

If you can understand this code, they reasoned, you can unlock the wonders of life.

Nobel Prize

Wilkins wrote to his rivals to congratulate them on winning what was at times a bitter race.

When he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine along with Watson and Crick in 1962, Franklin did not accompany them.

Her life was cut short by ovarian cancer when she was just 37 years old.

According to the rules of the Nobel Committee, only the living could be honored. Her fans believed that Franklin had been deceived twice.

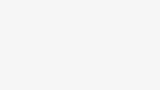

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWatson and his wife Elizabeth later moved to Harvard. He became a biology professor and had two sons, one of whom suffered from schizophrenia.

He then headed the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York State, a troubled institution that he is credited with transforming into one of the world's leading research institutions.

In 1968, his account of the race to discover the Double Helix structure of DNA was published.

This is a painful examination of history. It rake in personalities, contradictions and bitterness from his point of view. He was thinking of calling the book Honest Jim.

But despite all of Professor Watson's academic achievements, his subsequent career was overshadowed by his controversial public statements.

In 1990, Science magazine wrote that “To many in the scientific community, Watson has long been something of a wildcat, and his colleagues tend to hold their breath whenever he deviates from the script.”

At the 2000 conference, Watson proved this.

He put forward the idea that black people have more libido than white people. His lecture stated that melanin, which gives skin color, increases sexual desire.

“That’s why you have Latin lovers,” he told delegates. “You will never have an English lover, only an English patient.”

He suggested that humanity could weed out stupid people through genetic testing. Then he gave an interview that dealt the biggest blow to his reputation.

While promoting his autobiography, Watson spoke to the Sunday Times.

The article quotes him as “gloomy about Africa's prospects” because “our social policies are based on the fact that their intelligence is the same as ours, when all the tests say this is not entirely true.”

Watson went on to admit that this “hot potato” is difficult to deal with and he hopes everyone will be equal.

However, he said, “People who have to deal with black employees don't think that's true.”

He later apologized, but his research institute stripped him of executive power and kicked him out as honorary chancellor.

Scientific photo library

Scientific photo libraryJames Watson spent the rest of his life continuing to raise money for medical research, often tugging at heartstrings in a shameless manner.

“Nothing attracts money like finding a cure for a terrible disease,” he said.

He never failed to make waves by warning that “Viagra fights evolution.”

He also argued that men should store sperm during adolescence to avoid increasing the likelihood of having children with developmental disabilities.

He repeated his views on the connection between race and intelligence in a 2019 documentary, after which the scientific community stripped him of his remaining honorary positions.

He will be remembered as the “Godfather of DNA”, the man who unraveled the mysteries of life, and the world-class polemicist who often silenced him.