Millions of people across the Caribbean are struggling to cope with the devastating effects of Hurricane Melissa, which swept through the region this week.

Like many storms recently, Melissa experienced rapid intensification, defined as when a storm's maximum sustained wind speed increases by 51 km/h in 24 hours.

Melissa's speed increased by 112 km/h over the same period, an example of what some call extremely rapid intensification.

As we continue to burn fossil fuels, releasing CO2 into the atmosphere, the planet continues to warm, causing many changes in weather patterns and overall climate.

So what was the role of climate change in Hurricane Melissa?

Warm oceans

Scientists are increasingly analyzing the impact of climate change on severe weather events such as droughts, floods and hurricanes.

There are several organizations conducting their own analysis, including Environment and Climate Change Canada.

One of these organizations, which includes climate scientists from around the world, is Climatic meter. They conducted a rapid analysis of the causes of Hurricane Melissa and found that both climate change and natural variability played a role.

Hurricanes like Melissa have been found to be about 10 percent wetter and 10 percent windier than in the past due to climate change. Natural variability played a role in its formation and path.

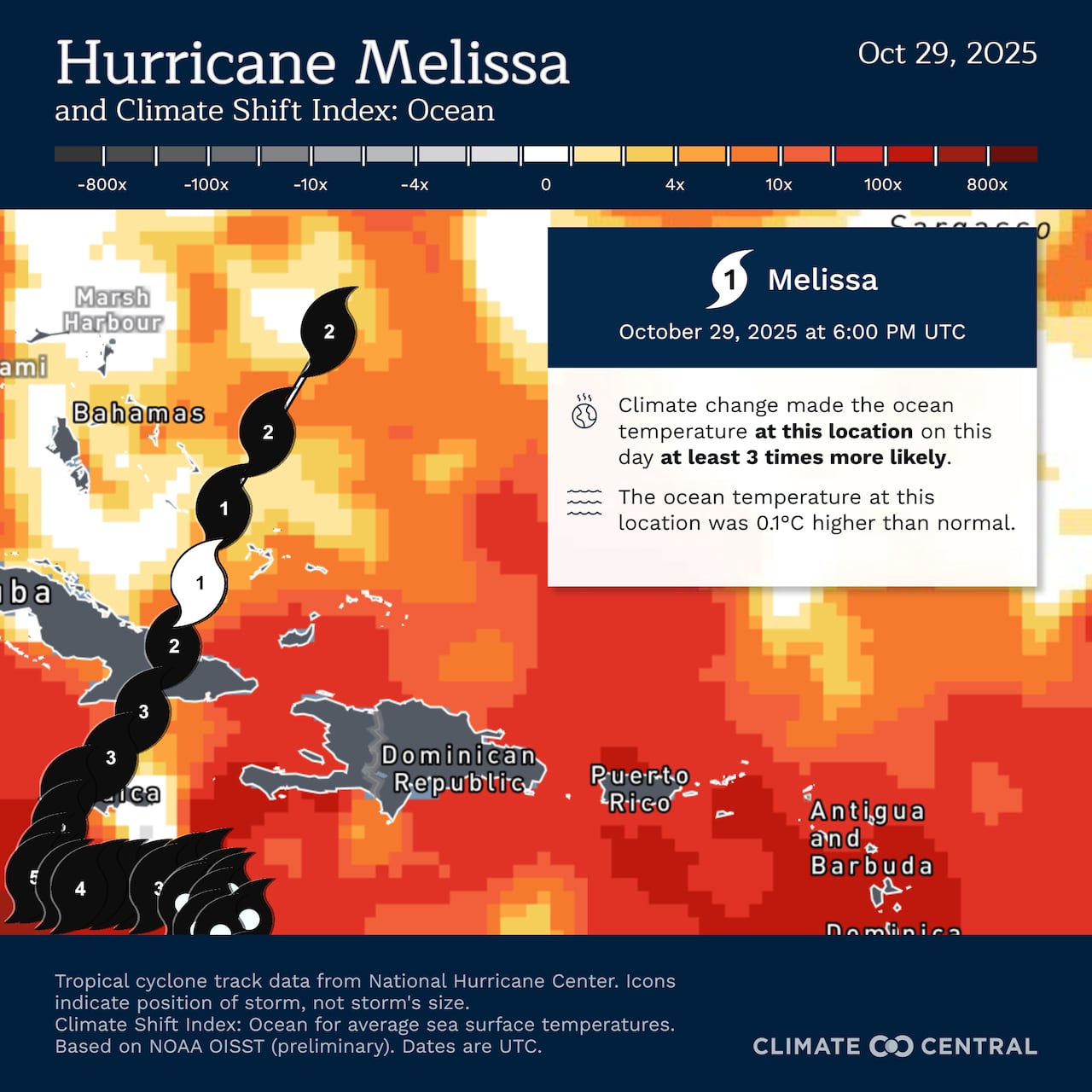

One of the main factors influencing climate change is the change in the health of our oceans. The temperature was historically warmer than usualand this warm water serves as fuel for hurricanes. The warmer the water, the more fuel.

Shel Winkley, meteorologist from Climate Centrala group of independent scientists who report on climate change said temperatures in the Caribbean were 1.4 to 2 degrees above average.

“We know that water temperatures at this time of year in this part of the Caribbean are 500 to 700 times higher because of the excess heat that we humans contribute to the atmosphere, which then sinks into the ocean,” Winkley said..

This, in turn, can encourage rapid intensification, as has happened with four of the five hurricanes that formed in the Atlantic Basin.

“It’s something we didn’t see a couple of decades ago, but now we see at least every season, if not even multiple times.” [a] season,” Winkley said.

Strong wind

Another independent analysis was carried out by the Grantham Institute at Imperial College London, which works on climate change and the environment.

Using Imperial College Storm Model (IRIS)The analysis found that climate change increased wind speeds in Melissa by about seven percent, or 18 km/h.

Video taken from aboard a U.S. Air Force 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron aircraft, also known as the Air Force Reserve Hurricane Hunters, shows what flying into the eye of Hurricane Melissa looked like Monday as the powerful storm approached Jamaica.

While many people focus on the rapid intensification of hurricanes, Ralph Toomey, director of the Grantham Institute and co-author of the analysis, said that's not necessarily what we should be focusing on.

“People talk about rapid intensification. I think… that's fair enough, but in fact it happened a few days before landfall… it quickly intensified to Category 4 within 24 hours,” he said.

“The other reinforcement was that as you got closer to the island, it actually became something more terrible because it essentially became a category 6… but we don't have that category because folklore says that anything over five does the same damage, basically total damage. So there's no need for that.”

The analysis also concluded that hurricanes of this type are four times more likely to occur than in pre-industrial times.

“We think it's like the pre-industrial period before the warming happened, it could have happened maybe 8,000 years from now,” Toumi said. “Even now [it] would be a once every 1000 or 2000 years event. So even now it is extremely unlikely, but then [the] According to the headline, this has essentially become four times more likely.”

In terms of destruction, the authors found that without climate change, a weaker hurricane would have been about 12 percent less destructive. (They haven't focused on damage estimates because it's too early to tell what those numbers will be.)

What does this all mean?

While the numbers may vary depending on the rapid attribution groups' methodology, the point remains the same: Climate change is changing hurricanes.

As we pump more fossil fuels into our atmosphere, the oceans, which absorb more than 90 percent of the excess heat trapped by greenhouse gases, will continue to warm and hurricanes will continue to wreak havoc.

Asked by CBC News what this means for the future, Toumi said: “I think what it says is that, you know, there are limits to adaptation. People say, “Oh, we should focus on adaptation and resilience.” And on some level there are definitely benefits.

“But you won’t be able to adapt to Category 5. It will cost you a fortune. Essentially, you won't be able to provide that kind of sustainability. So there are limits to adaptation.”