China is currently the dominant force causing and controlling global warming. Over the past decade, China is responsible for 90% of the rise in carbon dioxide emissions that are raising global temperatures. research shows. However, China is also at the forefront of the global green energy transition and filling the leadership vacuum left by the United States after Washington pulled out of international climate agreements.

For this reason, all eyes have been on Beijing's new climate pledge, presented at the UN last month.

On the one hand, this promise marks a step forward. For the first time, China has set an absolute target to reduce emissions rather than limit future growth. In addition, its commitment applies to all greenhouse gas emissions and economic sectors.

Why did we write this

China's new commitment to combating climate change marks a modest step forward for one of the world's most populous countries. It also shows how the bar for climate leadership is falling lower.

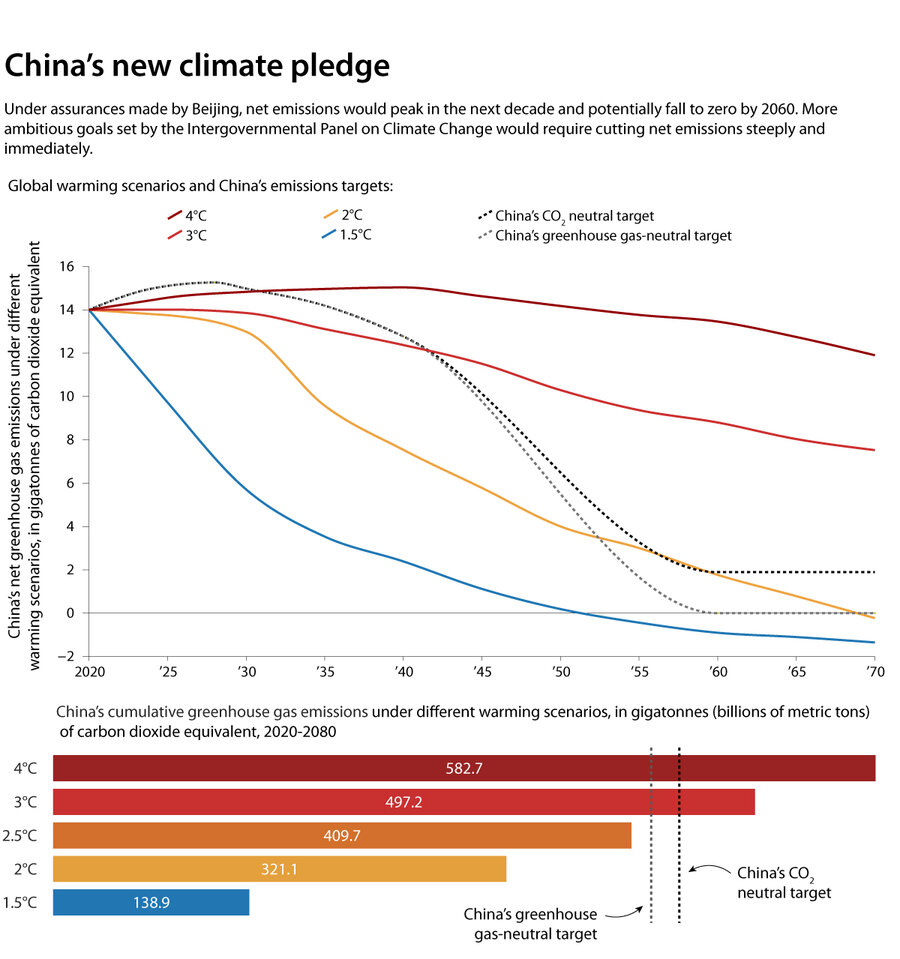

However, experts say China's commitments fall far short of the targets needed to meet the Paris Agreement's imperative to limit global temperature rise to less than 1.5 degrees Celsius.

What are China's new goals?

In a video message at the UN climate summit in New York on September 24, Chinese leader Xi Jinping said his country would cut its economy's greenhouse gas emissions by 7% to 10% from peak levels by 2035. Experts say China's greenhouse gas emissions reductions need to be closer to 30% to be on track to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement.

“The level of ambition… is quite low” given China's commitments under the Paris Agreement, and “particularly low compared to what they can deliver given the stunning clean energy boom taking place in the country,” says Lauri Myllyvirta, a senior fellow at the China Climate Center at the Asia Society Policy Institute.

Moreover, by tying cuts to an as-yet-undefined “peak” rather than a specific year, Beijing “risks creating an incentive for increased emissions” by communities and firms seeking to lock in fossil fuel capacity at a higher level, Mr. Myllyvirta says.

Xi Jinping also pledged that China will increase the share of non-fossil fuels in total domestic energy consumption to more than 30% by 2035 and increase installed wind and solar power capacity to 3.6 billion kilowatts, more than six times the 2020 level. Both goals are conservative, experts say.

Will China be able to achieve these goals?

China's track record tells us that it has the ability and willingness to achieve these goals. In fact, it has the potential to cut emissions even more dramatically, but leaders are proceeding with caution.

“The promise is a little modest,” says Yanzhong Huang, a professor at Seton Hall University's School of Diplomacy and International Affairs. “They seem to view it as a floor rather than a ceiling… They certainly don't want to over-promise.”

China's rapid progress in expanding its use of solar, wind and other renewable energy sources in recent years is the most important indicator that the country can cut emissions at a faster pace. For example, in 2020, China pledged to more than double its renewable energy capacity to 1,200 gigawatts by 2030, but ended up achieving that goal more than five years early.

“Wind and solar installations are at record levels,” says Dr. Huang. “In green technology, they've gone from imitators to innovators. They essentially dominate 80% of the world's solar panels. The progress has really been remarkable.”

Given these modest goals, can China lead efforts to combat climate change?

In the past, US-China competition has been an important motivator of Beijing's climate commitments. Today, the lack of U.S. pressure makes it easier for China to set the bar low for targets while continuing to sound a rallying cry for emissions reductions.

At the UN, Mr Xi indirectly referred to Washington's withdrawal from the Paris agreement, saying that “some individual countries are moving against the tide.” Instead, he called on the assembled leaders to “strengthen our resolve,” calling the green transition “the trend of our times.”

When it comes to addressing climate change, “the United States is doing much more than just abdicating the throne. It is ceding leadership to China,” says Gary Yohe, a professor of economics and environmental studies at Wesleyan University.

However, experts say it remains to be seen whether China can truly become a leader in the fight against global warming.

Overall, Beijing's decisions on climate commitments appear to be driven by domestic priorities, such as Xi Jinping's focus on energy security.

To hedge its bets, China is ramping up renewable energy while expanding its coal industry and producing more oil and gas, giving the country more energy than it needs.

Experts say Beijing's climate pledges indicate that the leadership has so far not decided to give a decisive priority to renewable energy sources or fossil fuels. But as green energy expansion continues, that could change, putting China on a path to “much greater emissions reductions by 2035,” Mr. Myllyvirta says.