People whose main reason blindness were able to read again thanks to a tiny wireless chip implanted in the back of the eye and special augmented glasses, according to study results published Monday in the journal New England Journal of Medicine.

The study involved 38 European patients, all of whom had advanced dry age-related macular degeneration (AMD), known as geographic atrophy.

There is no cure for AMD, which is caused by changes in a part of the retina called the macula and is caused by inflammation and waste buildup. Photoreceptor cells in the macula are responsible for clear, detailed and color vision. When the disease progresses to the stage of geographic atrophy, cells break down and die, and the person loses central vision – that is, an object directly in front of you may appear blurry or covered with a dark spot.

According to the World Health Organization, approximately 22 million people in the United States have AMD, and about 1 million have geographic atrophy. American Macular Degeneration Foundation.

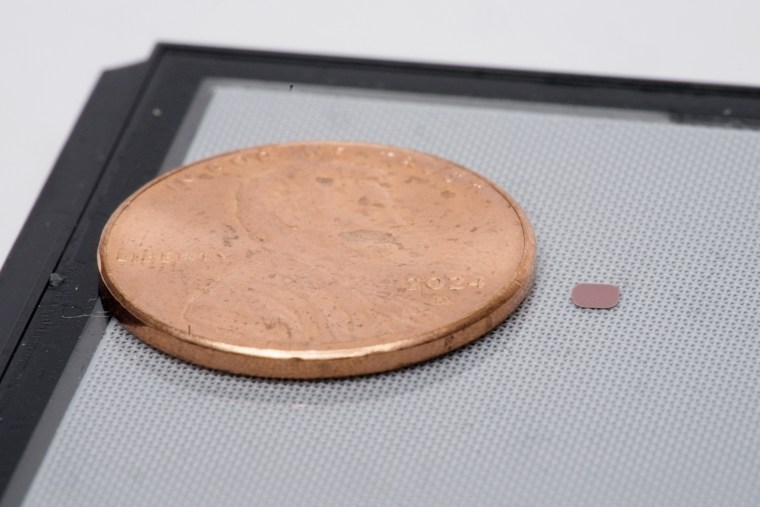

In the study, participants, with an average age of 79, were equipped with a “PRIMA device,” a system designed to replicate vision. Patients wear augmented reality glasses with a built-in camera that captures their field of vision. What the camera “sees” is transmitted to the chip implanted in the eye in the form of infrared light. The chip converts the light into an electrical current that realistically stimulates the remaining healthy cells in the macula, allowing the brain to interpret the signals the cells send as vision.

The image processor, which users must carry with them, allows patients to zoom in and out on the images they see, which are displayed in black and white.

With the PRIMA device, 80% of 32 patients who returned for a follow-up examination one year after chip implantation achieved clinically significant improvement in vision. Patients did experience side effects, mostly related to the surgical procedure: The study reported that 26 serious adverse events occurred in 19 patients, ranging from increased blood pressure in the eyes to blood pooling around the retina. Most adverse events resolved within two months after implantation.

“This is the first therapeutic approach that has resulted in improved visual function in this group of patients,” said Dr. Frank Holz, lead investigator of the study and head of the department of ophthalmology at the University Hospital Bonn in Germany. “Late-stage age-related macular degeneration is a grim disease. Patients are no longer able to read, drive, watch TV or even recognize faces. Therefore [these results] in my mind they change the rules of the game.”

One patient, 70-year-old Sheila Irvine, who had the PRIMA device fitted at Moorfields Eye Hospital in London, said in a statement provided by the hospital that her life before she received the implant was like “two black discs in her eyes with a distorted appearance”. Before she lost her sight, Irvine called herself an “avid bookworm,” and now she can do crossword puzzles and read recipes.

Dr. Suneer Garg, a professor of ophthalmology in the retina department at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia who was not involved in the study, said the results are a breakthrough for patients with geographic atrophy. All doctors were able to offer were visual aids, such as magnifying glasses, and emotional support, he said.

“Even with new medical treatments available, the best we can do is slow the progression of the disease,” said Garg, who works with several drug makers treating AMD, including Apellis Pharmaceuticals, the maker of pegcetacoplan. A drug that slows the progression of geographic atrophy was recently approved in the United States and must be injected into the eye every one to two months. “We can’t stop it and there’s nothing we can do to restore lost vision.”

Dr. Demetrios Vavvas, director of retinal services at Mass Eye and Ear in Boston, who also was not involved in the study, said the PRIMA system is not without limitations.

Vavvas noted that the operation to implant a chip in the eye requires a high level of surgical skill and is not without risk. “To implant this device, you have to tear the retina away from its normal position, which increases atrophy,” says Vavvas, a consultant for Sumitomo Pharmaceuticals, a company that develops stem cell therapies for patients with other forms of vision loss.

Vavvas said it was important to note that the device did not restore normal vision because patients could only see in black and white, not color, and that study participants had to undergo significant training to learn to see with the device. He also said it was unclear whether improvements in visual abilities resulted in significant improvements in patients' quality of life.

But at the same time, Vavvas was also optimistic about its potential, describing the current version of PRIMA as a key step in the field of vision restoration.

“Think of this device as a pre-release version of the iPhone,” he said. “The limitations are obvious. The fact that quality of life has indeed improved should not be overstated. But there were certain [visual] tasks that patients performed clearly better. This shows us that this approach has potential. In some ways it's still a prototype. They are working on better versions of this device.”

New updates to the device may arrive in the next couple of years.

The PRIMA system was invented by Stanford University ophthalmology professor Daniel Palanker and is being developed by California-based neural engineering company Science Corp.

Palanker said technical improvements are being made to increase the number of pixels on the chip from 400 to 10,000. The new chips have already been tested on rats, and upgraded chips are being produced for future human testing. Using the camera's zoom feature, this could theoretically allow patients to achieve 20/20 visual resolution, Palanker said.

“We are also working on next-generation software that will allow patients to perceive not only black-and-white text, but also natural grayscale images, such as faces,” Palanker said.

Palanker suggested the technology could be tried in other blinding retinal diseases, such as Stargardt disease, which has symptoms similar to age-related macular degeneration but is genetic and typically affects younger people.

Garg and Vavvas are looking forward to larger studies that will provide more detailed information about how the device improves patients' ability to function day-to-day. Vavvas suggested that future trials should include a control arm to understand the extent to which the device provides real benefits, for example, compared to existing electronic magnifiers.

“Is this enough for patients to say, 'Well, I've regained my independence because now I can pay my own credit card bills, stamp and address envelopes myself, and look at grocery store labels'?” – said Garg. “These are practical things I would like to know more about.”

Vavvas said: “This is a chronic disease that you will have for the rest of your life, so we need more than one year of follow-up to see other risks, other problems. Does that signal of effectiveness that we see at 12 months still exist two years later?”

Although Vavvas said he would not call the device a panacea for blindness, the study found that brain-computer interfaces may represent an important approach to addressing various types of severe visual impairment. “As versions of this device get better and better, it could become a real solution for a cohort of patients,” he said.