As Israel continues to launch air strikes on Gaza, the weakness of both the ceasefire and Trump’s 20-point plan are becoming ever clearer.

On Sunday, October 19, Israel launched massive air strikes across the Gaza Strip, killing 44 Palestinians. It was the 48th time Israel violated the ceasefire and brought to at least 97 the number of Palestinians killed by Israeli fire since it was declared 10 days earlier. Israel suspended all aid from entering the Strip but then agreed to resume deliveries. While both Hamas and Israel have since reaffirmed their commitment to the ceasefire deal, it remains almost impossibly fragile. The genocide is not over.

The ceasefire’s weaknesses have been evident from the beginning. There was always a strong possibility Israel would resume its pulverizing assault on Gaza once the living hostages were released. The Israel-Hamas agreement—signed only after the narrow ceasefire and hostage exchange were separated from the rest of Donald Trump’s 20-point plan—did not call for the withdrawal of Israeli troops from Gaza. It provided no guarantees that the promised 600 daily truckloads of humanitarian aid would be allowed to enter. And while it called on Hamas to return all bodies of deceased hostages within 72 hours, it imposed no consequences if Israel refused to allow in the heavy equipment needed to dig them out from under Gaza’s rubble. Crucially, it provided no protection for Palestinian civilians if—or when—Israel resumed its killing spree.

The early days of the ceasefire provided Gaza’s 2 million people a few days of respite from Israel’s constant killing and its deliberately imposed starvation and famine. If it holds, it could mark the end of the worst phase of Israel’s brutality in the Strip. But we should have no illusions about its prospects—or about what lies ahead for the people of Gaza.

What has actually been decided and agreed to in these recent days of US-orchestrated diplomacy?

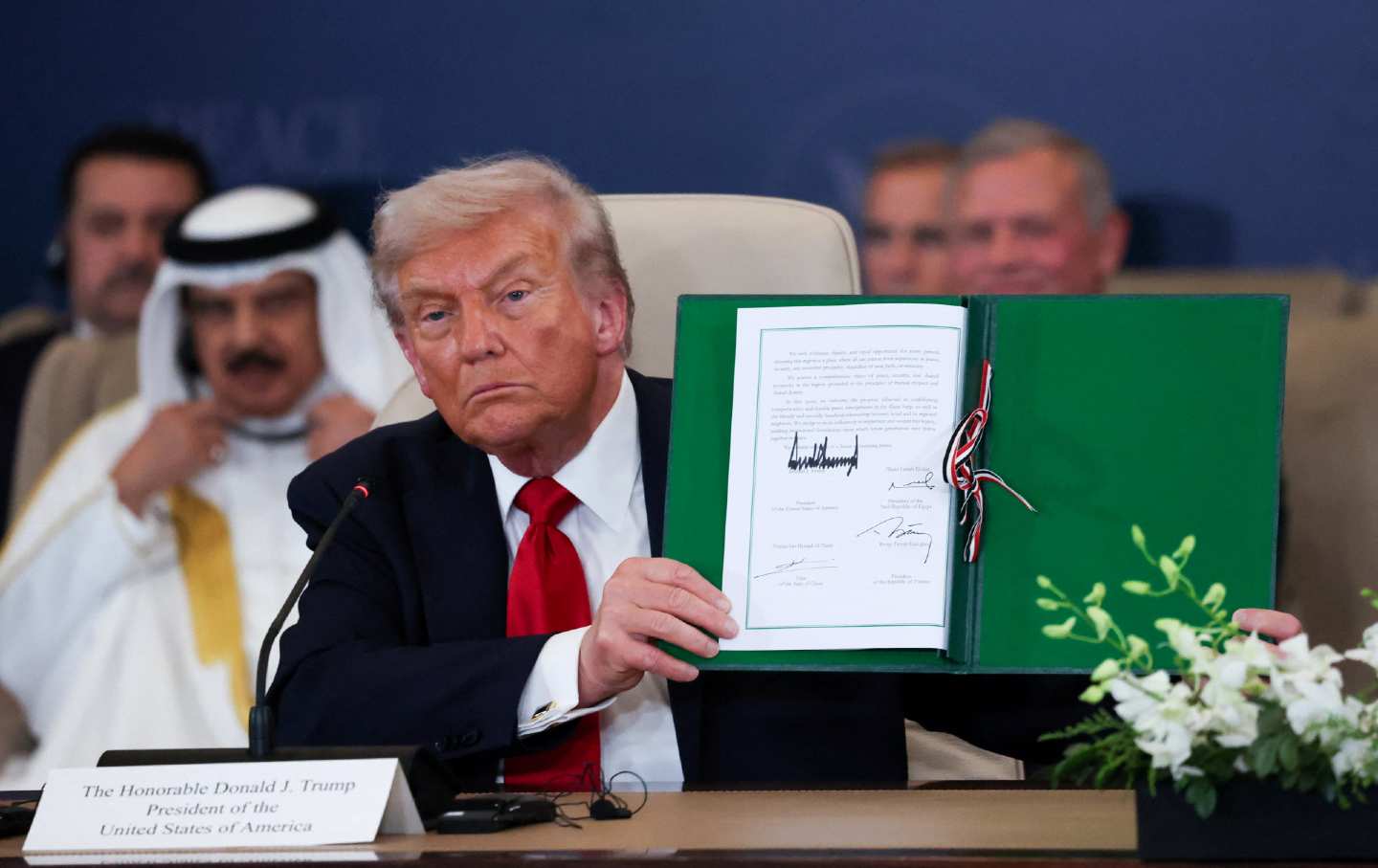

The bottom line is that Israel and Hamas signed only a brief ceasefire agreement that called for an “end to the war” without defining what that meant. They also agreed to “full” access to humanitarian aid, the redeployment of Israeli troops slightly farther east inside Gaza, and the exchange of Palestinian and Israeli captives. At Trump’s hastily convened celebration in Sharm el-Sheikh, the invited guests were primarily US-backed Arab monarchs, right-wing politicians from several countries, a line-up of Europeans, and others. They watched as Trump and leaders from Qatar, Türkiye, and Egypt signed off on what was called the Trump Declaration for Enduring Peace and Prosperity, a vague statement of support for Trump’s earlier 20-point plan.

The operative assumption seems to be that Trump’s 20-point plan will be the framework for the “peace” that will ostensibly follow the ceasefire, if it holds. It is supposed to start with the creation of what is being called the Gaza International Transitional Authority, a frankly colonial body that is all too reminiscent of the Iraq Coalition Provisional Authority that the US imposed after its 2003 invasion, to disastrous effect for that country. Trump’s GITA would be chaired by none other than Donald Trump, possibly alongside Tony Blair of Iraq War lies fame, as well as a lineup of international billionaires.

According to a leaked diagram of the anticipated hierarchy, the GITA would have control of grants, finances, investment, and economic development. Its Investment Promotion and Economic Development authority would be tasked with “generating investable projects with real financial returns” as well as “attract[ing] private capital” and “manag[ing] investment portfolios.” It would also feature a Grants and Financial Accountability Facility that would “receive, hold, and disburse all grant-based contributions” that might come from international donors. Lots of profit-making potential—but no mention of providing economic survival, let alone improvement, for the people of Gaza.

Beneath these entities would be a series of commissions to deal with reconstruction as well as humanitarian, security and other issues.

This whole structure would be protected by an international “stabilization” force—not a protection force to provide security for Palestinians in Gaza living under foreign occupation but, rather, to protect Israel and Egypt from any potential Palestinian resistance. (The GITA bureaucracy would have its own “executive protection unit” to keep those billionaires safe.)

And at the very bottom of the hierarchy, the plan calls for the creation of a committee of US-vetted Palestinian technocrats (no indication anyone in Gaza will have any say in choosing them) to run day-to-day affairs in Gaza. That committee would be completely under the control of layers of bureaucrats right up to the GITA at the very top.

It is, essentially, equivalent to the imperial mandates handed out by post–World War I European powers as they redivided their colonial empires. And it means continuing occupation of Gaza.

Crucially, the plan does not call for the immediate withdrawal of the Israeli military from Gaza, only redeployment slightly eastward in phased steps, ultimately ending with a wide buffer zone. It provides no Palestinian control of borders, water, economy, airspace, coastal waters and their resources (including massive gas reserves), or even foreign policy. It offers nothing more—and perhaps even less—than a return to the grim reality of Gaza on October 6, 2023.

The plan violates a host of rulings by the International Court of Justice, ignores resolutions of the United Nations General Assembly, and ultimately ignores international law. It sweeps away eight decades of the vision—with all its limitations and inadequacies—of the United Nations, and even goes beyond the so-called “rules-based order” that has replaced international law in far too much political discourse in the United States and Europe. Instead, it inaugurates a new order that seems to be based on the notion that the US president’s prerogative includes the power to declare that “the war is over now,” on his own terms, regardless of whether the genocide has really ended. It’s beyond a rules-based order; it goes straight to the rule-by-fiat of a crime boss.

And that sense of absolute power and entitlement—handpicking how a war ends, deciding who’s in charge, choosing what roles his real estate friends and family might play—extends to what the post-genocide Gaza governance might look like. In response to Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi’s diplomatically popular (if utterly impracticable) argument that a two-state solution is “the only way to peace in the Israel-Palestine conflict,” Trump took a whole different tack, one rooted in his own power. Speaking to reporters on his flight back from Sharm el-Sheikh, he said, “I’m talking about something very much different. We’re talking about rebuilding Gaza. I’m not talking about single state or double state or two state…. A lot of people like the one-state solution. Some people like the two-state solution.… At some point I’ll decide what I think is right.” He felt compelled to add that “I’d be in coordination with other states”—but certainly not in coordination with any Palestinians. He will decide.

Israel is in a different position from where it was two years ago. While the attack of October 7 pierced its long-standing sense of invulnerability, it is now riding high, confident both in its military prowess and the complete support of the United States. While the capture of hostages served as a living wound, reminding Israelis of their vulnerability, the return of those still alive is ending that fear. Israel is ready to move on, continuing to devastate Gaza and facing no accountability for the harm it has already caused

The Trump plan aims to help it do that. While it goes into great detail about how the people of Gaza under foreign occupation will be constrained and controlled, it says almost nothing about constraining or controlling Israel—leaving out, for example, any reference to the urgent need for ending arms transfers that enable Israel’s genocide. Or for that matter, it’s many other military campaigns.

Israel remains more militarily aggressive than at perhaps any time in its history. In addition to the genocide in Gaza, it continues to wage a ferocious military assault—in concert with armed settlers—in the West Bank; to drop bombs on Lebanon and seize Lebanese territory; and to attack Syria and seize Syrian land (beyond the Syrian Golan Heights that Israel has illegally occupied and colonized since 1967). Israel is bombing Yemen, has carried out a wave of bombings in Iran, and bombed Qatar. While most Israelis supported a ceasefire in Gaza to secure the release of captives, these other military operations across the Middle East are popular with the Israeli public.

There are those proponents of Israeli violence who mistake the state’s aggression for untrammeled strength and dismiss the overwhelming, global outrage it has engendered. Right-wing columnist Bret Stephens argued in The New York Times that, “for all the global street protests, hostile op-eds and meaningless arms embargoes, they have the full-throated backing of the only foreign government that matters: America’s.”

But Israel is facing repercussions for its actions, and its global isolation is stark. The walkout of scores of delegates during Netanyahu’s speech at the latest UN General Assembly was one expression of global outrage with the genocide. Some governments have seriously pursued the end of Israel’s impunity, such as South Africa—which led the case accusing Israel of genocide at the International Court of Justice—and its fellow members of the Hague Group of Global South countries that have suspended weapons and other trade with Israel. While too few governments have taken any real actions to stop the genocide, many have been compelled to denounce it, lest they lose all credibility among their populations. Trade agreements and other arrangements with Israel have been sources of embarrassment requiring damage control, as those countries’ residents demand consequences for Israel’s actions. This—the mobilization of movements and global civil society—are the driving forces of Israel’s isolation.

As a result, Israel is facing more repercussions for its atrocities than ever in history. Israeli sports teams are being disqualified from competing around the world under their flag. Its prime minister was forced to take a circuitous route on his latest flight to Washington to avoid the airspace of countries where he might be arrested and sent to The Hague. And its surveillance apparatus has lost access to some provisions of Microsoft’s Azure data system—a development that is causing panic among some proponents of Israeli power because it reveals the country’s dependence on other states and their corporations.

So what is needed now? We still don’t know if the current level of Israeli violations of the ceasefire agreement will continue, or even if the incomplete ceasefire will hold at all. We don’t know if Israel will agree to allow in at least the modicum of humanitarian aid Netanyahu promised in the agreement. We don’t know if Tel Aviv will allow in the critical amounts of fuel and heavy equipment to begin the search and retrieval of at least some of the thousands of Palestinian families buried under the rubble of their homes, along with the bodies of Israeli hostages.

If none of that happens, we have to continue to make the call to end the genocide our central demand. All those things must happen now, today.

And whether or not those efforts are accomplished, we need to keep pushing, more forcefully than ever, to stop the currently unlimited flow of arms to Israel. It is those US weapons that will allow Israel to resume its genocidal assault on Gaza and the West Bank whenever it chooses, confident that Trump is unlikely to act to do anything to stop it.

That means ratcheting up our efforts to get Congress to pass the Ban the Bombs Act in the House and to match it in the Senate, and to continue the push for Joint Resolutions of Disapproval when any new weapons shipments come up for approval. It means building and strengthening the US and global BDS campaigns aimed at stopping the shipment of arms to Israel, including efforts to make the transportation of weapons and fuel for weapons more difficult. And it means that, as the global isolation of Israel grows, so must our demand for a full withdrawal of Israel’s troops from Gaza, and the end of Israeli occupation and apartheid.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Alongside all these demands, it is essential that our movement continue to sound a parallel call for accountability. That means supporting South Africa’s case in the ICJ to hold Israel accountable for violating the Genocide Convention. It means bolstering the work of the UN General Assembly as well as powerful new coalitions such as the Hague Group led by South Africa and Colombia, and civil society initiatives such as the Gaza Tribunal, to encourage countries to impose arms embargoes, trade and banking sanctions, and diplomatic pressure to push Israel to end its violations of international law.

And it means civil society and social movements must mobilize harder than ever before to build a movement powerful enough to bring an end to Israeli genocide and apartheid. We have a model in the 1980s anti-apartheid mobilizations against South Africa. The United States vetoed resolutions at the Security Council, dismissed General Assembly resolutions as unenforceable, until enough individual governments, under pressure from growing anti-apartheid movements in their own countries, acted on their own. They ended arms sales, imposed sanctions, cut off trade relations, moved to cancel apartheid South Africa’s right to speak or vote in the General Assembly. And eventually, especially when US allies joined the movement, the US was forced to follow along. Our movements became the enforcers of international law.

We can do it again. We have no choice but to try.

More from The Nation

The use of airpower to try to subdue or at least curb Middle Easterners is, in fact, more than a century old.

A so-called precept in the practice of news coverage is that “if it bleeds, it leads.” Well, apparently, if a Palestinian is bleeding, this isn’t true.

Amid a spiraling political crisis, France’s president is being forced to retreat on his signature reform.

An industry built on addiction and loss now commands enormous political and cultural influence, from NFL stadiums in Philadelphia to soccer stadiums in São Paulo.