ABOUTAccording to him, one of the first sources of inspiration for artist, writer and director Michael Benson was the sci-fi epic. 2001: A Space Odyssey. Not only did the film spark wonder in his childhood, he says, but it also instilled in his six-year-old brain that grand themes like our role in the universe and our seemingly inexorable need for exploration were worthy topics for art rather than “merely” science or philosophy. This later raised questions in Benson about humanity's place in space and time, topics he has explored in his work over the last quarter century.

“My goal for quite some time has been to use the methodologies and technologies of scientific research to study the phenomenal world, not as a scientist, but as an artist and image-maker,” says Benson. His latest book Nanocosmoszooms in on tiny specimens, including single-celled organisms such as radiolarians (zooplankton) and diatoms (phytoplankton), insects, microscopic flowers and snowflakes, to highlight the intricacies of the natural world at the microscopic level. Paying tribute to our planet's place in the much larger cosmic world, it also includes photomicrographs of lunar samples collected during the Apollo program. The book contains 300 highly detailed images. built from scanning electron microscope scans taken over six years at the Canadian Museum of Nature. Nanocosmos it is both a journey into the infinitesimal landscapes of the Earth and a reflection on how humans visually explore and represent the physical world..

If you massage the bridge of your nose, you are touching a piece of the solar system.

In earlier projects, Benson focused on the universe around us, exploring the solar system and deep space phenomena before turning the lens back to Earth to explore the complex microscopic worlds at our fingertips. He has organized a series of large-scale shows of planetary landscape photography around the world, and has also produced films and written books, including A Space Odyssey: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke and the Making of a Masterpiece. Benson worked with director Terrence Malick on the film's visual effects. Tree of Lifecreating episodes loosely based on his first two books, Outside (2003) and Far (2009).

I recently spoke with Benson about the magic of photography, the intrigue of dung beetles, and people's attempts to visualize the universe.

What is the origin story of this book?

It's interesting that you use the term “origin story” because one of the key sections of the book is the study of various single-celled aquatic organisms. There is a kind of synchronicity between the origin of life and the book's origin story, which attempts to show some of the complexity and fascination of single-celled organisms, the modern evolutionary descendants of the origin story of life on Earth. And the larger origin story for me is my personal fascination with the special qualities of photography and microphotography and the way they allow the mechanically produced image to be used as a tool for personally directed explorations of phenomenal reality.

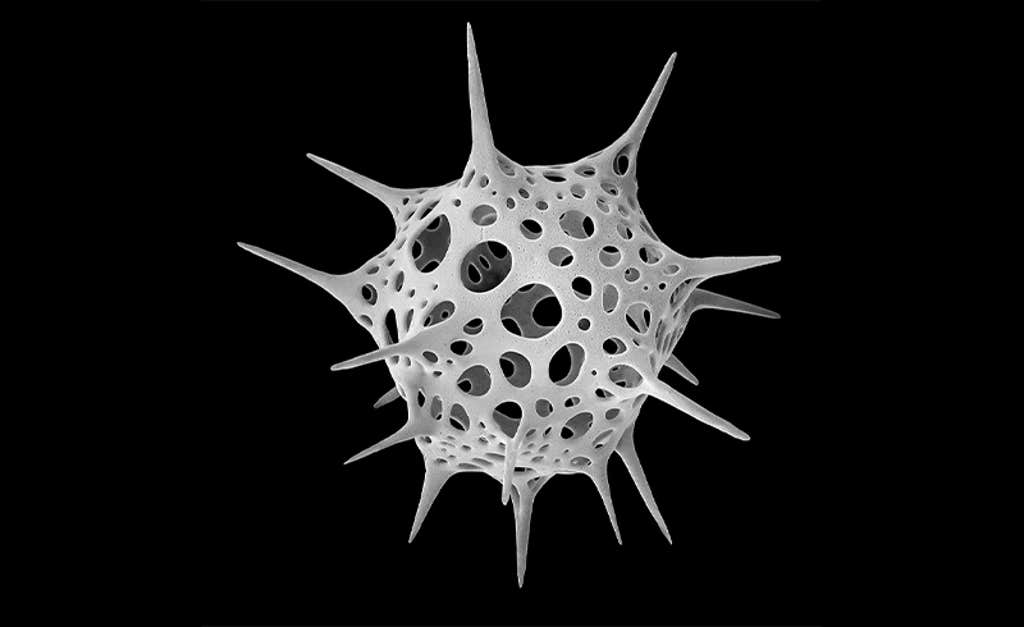

Around 1830's Width 120 microns, 0.12 millimeters.

How did you choose the topics for the book?

Some of them were just spontaneous. In the book, I talk a little about how ridiculous it was that I wandered around the tropics or the Adriatic coast with tweezers and vials of ethanol, looking for something that intrigued me while my family was swimming at the beach. Or, in the Caribbean, we just look in the rainforest for microflowers and little things that might jump out. But on the other hand, I perfectly understood that radiolarians, diatoms and dinoflagellates would be interesting. There was plenty of evidence of this, starting with a German marine biologist. Ernst Haeckel in the 19th century.

Many of your previous works have focused on planets and other objects in the Universe. How did you manage to go from the vastness of space to the smallest particles of life on our planet?

Well, this may sound pretentious, but collectively I consider all the books I've written for Abrams Books to be something of a complete work of artis a German word meaning a complex work of art that has many facets and synthesizes many genres. Like them Nanocosmos This is also space exploration, only on a different scale. Because, you know, if you massage the bridge of your nose, you're touching a piece of the solar system. So, all these fantastic objects that I was lucky enough to look at are part of the solar system. It's part of the larger phenomenon of spacetime and the wonder of how we're here to observe it in the first place.

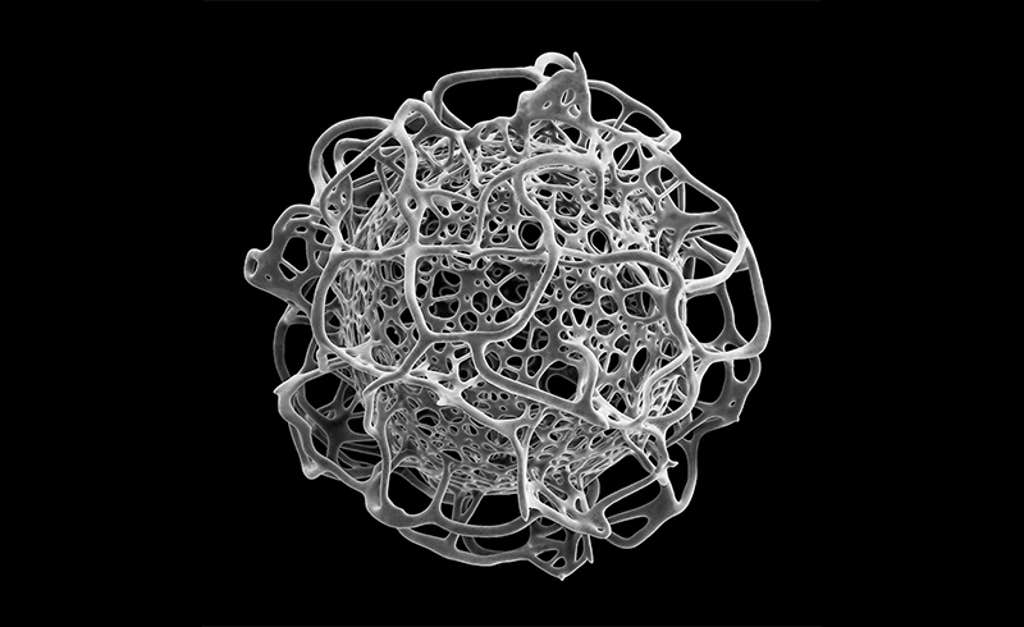

About 700 x. Width 300 microns, 0.3 millimeters.

Did any of the specimens you pictured surprise you?

If I had to pick one topic that really struck me in a way I didn't expect, it would be dung beetles. They roll out these giant balls of dung, sometimes over a quarter of a mile, and bury them. They are so perfectly designed to push something much larger than themselves. They look like the most unusual, powerful and living manifestations of the need to move weight. Not only that, they are so beautiful. The fact that these bulldozers can take off and fly is simply a miracle. In general, insects are simply magnificent under the microscope.

Do you understand why there are so many patterns and shapes tend to repeat themselves in nature, and what does this say about the world around us?

I'm not sure I completely agree, keeping in mind that nothing else on Earth looks like radiolaria, with its polygonal quartz shell, irregular polygons riddled with radiating spines. Nothing on a larger scale I've ever seen looked like this. The same is true for dinoflagellates and diatoms. These are very specific solutions for their ecological niche. But when you look at them, there can be a very mathematical, geometric sense of connection to larger principles.

How Nanocosmos build on past projects?

Nanocosmos this is a continuation of how we use images to understand the universe. What I mean is that there is a symbiotic relationship between representation and understanding. Photography has always been alchemical in a certain sense. It is a form of magic in which physical materials such as chemicals and photographic emulsions can be used to record other physical materials and chemical reactions, by which I mean the wider physical world. As humans, we represent the way the universe views itself. It's no surprise that we've created more powerful technologies that allow us to do this better, deeper, and with greater magnification. My other books cover things from the solar system to the Big Bang and the history of man's attempts to visualize the universe in graphical form. Nanocosmos links directly with them.

What was the process of creating the images for your book?

Due to the large amount of interplanetary material, the number of pixels in the images obtained from the spacecraft was not that large. Therefore, they had to be combined and composited to obtain higher resolution. When I finally had access to a scanning electron microscope and had virtually unlimited resolution, I went overboard and started scanning a lot. All this resulted in a huge amount of work, during which I had to assemble the final composite images. There's also a whole series of pictures where you see insects and plants together, but they're not as natural as they might look, in the sense that they were put in ethanol and then dried in what's called a critical point dryer, which is a way of replacing a liquid with a high-pressure gas with minimal damage to the object. If I didn't break the object, there was another delicate operation that involved mounting the object onto a small sample and placing it in a spray machine, which coats the samples and they end up looking like jewelry because they are plated with platinum or gold. Then you put it in the vacuum chamber of a microscope, and you have to learn a whole new range of things and problems associated with imaging the object. This is a labor of love.

What do you hope people take away from this work?

I don't want to prescribe anything. But I will be satisfied if people come away with a sense of amazement at the complexity of forms that nature can create on such an extremely tiny scale. And if it helps increase understanding of the biosphere that created us, that we don't treat with the respect it deserves, I'll be satisfied. Perhaps this can promote awareness that we really need to do a better job of improving the environment.