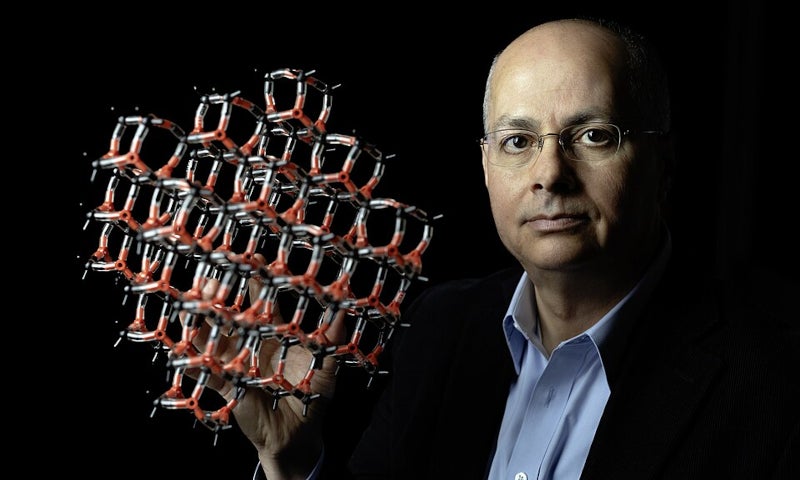

GAt the time of the row, Omar Yaghi shared a room with his siblings (and a small amount of livestock) in Amman, Jordan, with no access to running water or electricity. The son of Palestinian refugees who “barely knew how to read or write,” the UC Berkeley researcher was captive chemistry at a young age after studying “stick and ball” models of molecules in the library. This week Yagi received share of the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work on revolutionary materials called metal-organic frameworks.

Yagi excited to the United States at age 15, first attending community college and then earning a Ph.D. in chemistry from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. His path is not unique: half of this year's US Nobel Prize winners in science immigrants. Researchers with stories similar to Yaga's have contributed to the country's global scientific ascent for generations. But with increasingly restrictive immigration policies and science funding austerity imposed by President Donald Trump's administration, the nation's top research ranking—and future Nobel wins—hang in the balance.

“The Trump administration has systematically discouraged international students and undermined the research infrastructure that attracts them,” says James Witte, professor emeritus at George Mason University and former director of its Institute for Immigration Studies. “These students will find their academic home elsewhere.”

“I think we will definitely see a long-term decline in science in the US as a whole, if Nobel laureates are anything to go by.”

The US has not always been the academic powerhouse it is today. Before World War II, Nobel laureates mostly came from European institutions—until the 1930s, they were scientists associated with US institutions. received less than 12 percent of all Nobel prizes in science. But as the country invested more in research and conflict rocked Europe, foreign scientists increasingly migrated to the States. The most famous of these exoduses included Albert Einstein, who escaped Nazi Germany and eventually landed in the United States, and Enrico Fermi, who fled Fascist Italy by attending the Nobel Prize ceremony in Stockholm and from there fled to New York. At that time, most of the researchers who emigrated to the United States were from Europe, some of whom, like Fermi, contributed to the Manhattan Project.

This trend has helped propel the United States to scientific supremacy. From 1941 to 1950, researchers working at US institutions accounted for 47 percent of all Nobel laureates in scientific categories, 19 percent were immigrants.

“This was the period when the United States began its golden age of science and innovation,” says Ina Ganguly, an economics professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

In the 1960s, more scientists from Asia, including India and China, began to come to the United States. This coincided with the abolition of immigration quotas affecting Asian countries and a decade later with the opening of China's economy. The share of Nobel laureates in the United States peaked between 1991 and 2000. During this period, American scientists made up 72 percent of all academic Nobel laureates—a quarter of these laureates were immigrants.

Researchers and students from around the world continue to flock to the United States in search of generous academic opportunities. After earning their doctorates, most international STEM students settle here and begin their scientific careers, with some working their way to the Nobel Prize or other honors over the decades. One study examining the career trajectories of young International Mathematical Olympiad medalists found found that those who immigrated to the United States had more productive careers than those who moved to other countries. This higher productivity in the US is likely due to more abundant resources and opportunities, says Ganguly, one of the paper's authors.

Beyond awards, immigrants have a huge impact on innovation: In 2011, 76 percent of patents awarded to the nation's top universities “had at least one foreign-born inventor on the team,” according to report from the Partnership for a New American Economy.

But over the past two decades, the share of international students at U.S. universities and colleges has declined. That's likely due to rising school costs, Witte says, which are especially prohibitive for people coming from low- and middle-income countries. The Covid-19 pandemic, as well as the strict immigration policies of the first Trump administration, likely also played a role, Ganguly adds.

Now the Trump administration's increasingly restrictive policies could worsen the slowdown in the flow of global academic talent to the US, attacking academia on multiple fronts. First, deep cuts and freezes in federal funding threaten research programs that have long attracted people from around the world. It's just getting harder to get here. The administration presented travel bans and restrictions affected nearly 19 countries this summer. build-up verification of student visas and recently attached huge fee of 100,000 US dollars to H-1B visa applications. This latest policy change could cause “catastrophic harm” to research in the US, higher education groups say. who recently filed a lawsuit disputing the fee.

The potential impact on the U.S.'s Nobel Prize chances likely won't be obvious at first, says Patrick Gaul, an economist at the University of Bristol in Britain who co-founded the Global Talent Fund, a nonprofit that supports STEM students around the world. Over time, more young students will be able to attend universities in countries other than the United States, taking their award-winning knowledge with them.

“It's a very long gestation period for Nobel laureates,” Gole says, because it can take decades before research matures to the point where it is recognized by these awards.

But the exodus of scientists already at a higher stage in their careers may yield more immediate results, Ganguly says. Even in the early days of Trump's current term, Canada and Europe were courtship US scientists. Seventy-five percent of US scientists surveyed by the magazine Nature said they were considering leaving the country, according to the report survey published in March.

“If we go at this rate with a lot of [immigration] restrictions, then I think we will definitely see a long-term decline in science in the United States as a whole—by the standards of Nobel laureates,” says Ganguly. “The big question is how soon will it happen?”

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter

Main image: AntonSAN / Shutterstock