Jenny ReesWelsh Health Correspondent

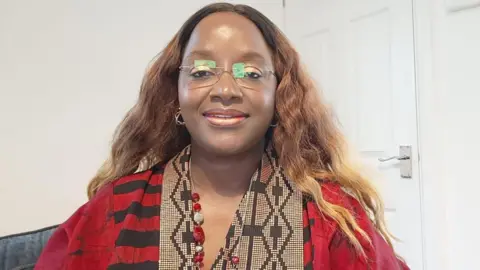

Bami ADENIBE

Bami ADENIBE“When the menopause enlightenment happened, women of color still weren't part of the conversation,” says Bami Adenipekun.

The 49-year-old investment adviser said she believes her brain is now “more fantastic than ever” and is celebrating its “most powerful season yet”.

But she said it took her a long time to realize that symptoms such as memory problems were related to menopause after cancer treatment when she was in her 30s.

Although research is limited, research has shown that ethnic minority women experience the menopause differently to white women – and this will be explored at an event for 'marginalized people and the menopause' in Cardiff later this month.

Dr. Amara Naseem will speak at the event World Menopause Day in Cardiff on October 18th.

In her experience as a GP in one of the most diverse areas of the Welsh capital, ethnic minority women are also less likely to seek help for symptoms than her white patients.

This is of particular concern to her given the prevalence of diabetes in South Asian communities, as a lack of estrogen can cause insulin resistance, meaning those going through perimenopause have an increased risk of developing diabetes.

“That's why I would tell women to prepare because our bodies are different and because of our ethnicity our risks are different as well,” she said.

What is menopause?

Menopause marks the end of a woman's reproductive period and usually occurs around age 51.

The lead-up to this event is known as perimenopause. On average it starts at 46 years of age.

This is when many women notice that their periods become unpredictable—heavier, lighter, longer, or shorter—and experience feelings or physical problems they didn't have before.

The event's project manager, Sahir Ahmed-Evans, said she hoped it would spread accurate information to women from ethnic minority communities, but most importantly to women who look like them.

The 47-year-old menopause coach said she now understands that her perimenopause symptoms began when she was 30, but the medical menopause two years ago came as a shock to the entire system.

“I thought I was dying,” she said.

“But after a few months, it was like a silver lining for me.”

She had lived with undiagnosed endometriosis and adenomyosis for years, so the injections that brought her through menopause felt like a “freedom” from her symptoms and a chance to reset and focus on her health.

“As a Pakistani Asian woman, I'm a mother, I'm a grandmother, I'm a wife, I'm a business owner, a content creator, and you just give and give and give,” she said.

“Then your body says, 'But there's nothing left, when are you going to give it to yourself?'

“So I feel like it's a natural way of saying, 'Now it's time to step back and take something for yourself.'

In addition to various physical symptoms, she said, there can be cultural pressure and stigma in some black and Asian communities where women's health can be a taboo topic.

Bami agreed, saying: “If they talk about it as a rite of passage, then what should we do?

“The older generation will say you just have to be strong because they were never told you could get help.”

But she believes systemic racism is a view recognized in race equality action plan for Wales – only serves to further disadvantage women.

Her own experiences in the workplace left her feeling “vilified and severely punished” when symptoms affected her cognition, pain levels or emotions.

Dr Naseem said creating a safe space to discuss topics such as vaginal dryness, itching or loss of libido is also crucial.

“Women from marginalized communities may not be very open to talking about these things,” she said.

“It’s so important for us to provide a safe space for these women.”