Could life exist elsewhere in the universe?

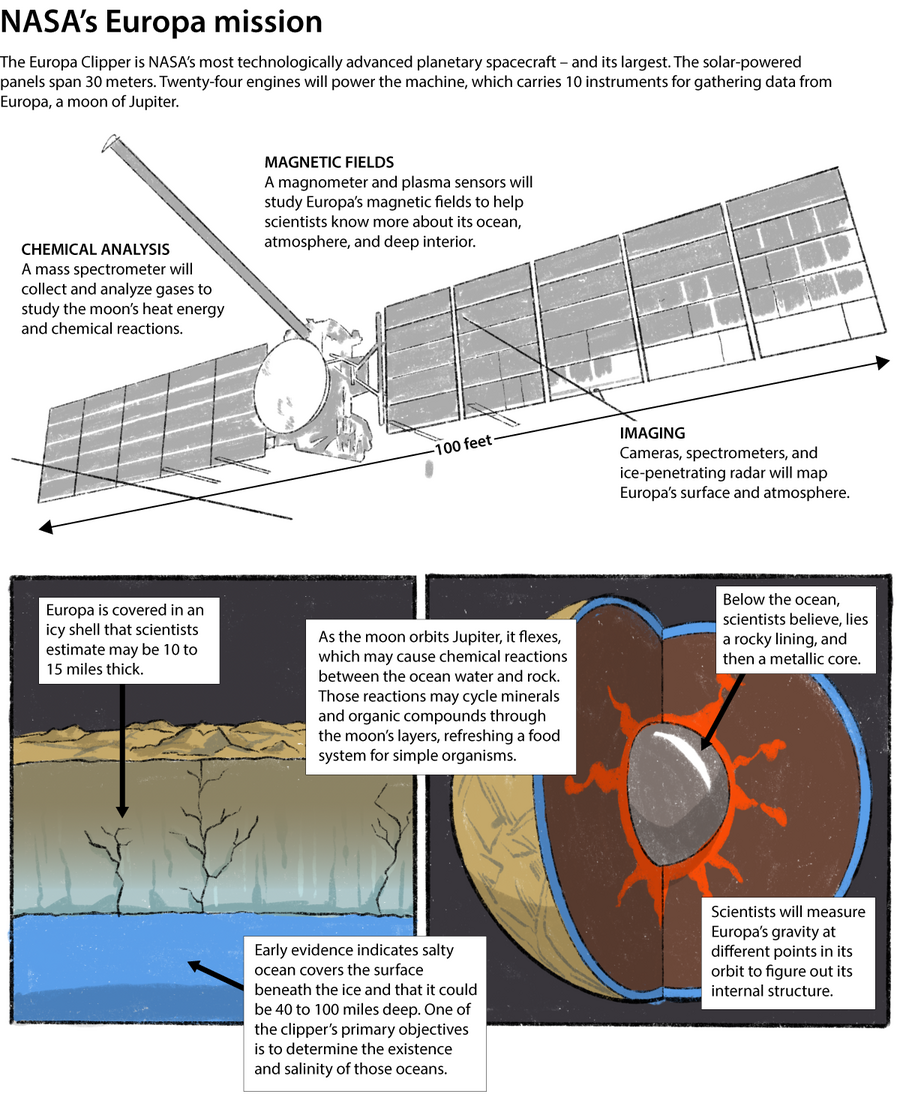

Scientists are one step closer to figuring out whether Earthlings are alone in the universe with the launch of NASA's largest and most technologically advanced planetary spacecraft, Europa Clipper, on October 14. The Clipper will head to Europa, one of Jupiter's more than 95 moons, to determine whether the celestial body supports life as we know it here on Earth.

The Clipper took 10 years to create, and it will take another 5.5 years to reach Europe. Over 49 flybys that will take 3.5 years, the Clipper will send back data allowing scientists to study Europa's oceans, rocks and atmosphere. Scientists believe that the oceans, in particular, are similar to those on Earth and will be a good indicator of the possibility of life there.

Why did we write this

The launch of the Europa Clipper mission to a potentially habitable celestial body – a moon of Jupiter – is a step forward in the search for an answer to one of humanity's greatest questions: is there life beyond Earth?

Erin Leonard has been part of the Clipper mission since its inception. The planetary geologist and Project Clipper scientist spoke with the Monitor about the mission's science and objectives, and what it all means for humanity.

The discussion has been edited for clarity and length.

What exactly are you looking for? What will indicate living conditions?

The question arises whether Europa has some sort of nutrient cycle that could support life.

I explain it the simplest way: water plus stone plus energy plus time. We have water that we think is similar to ocean water on Earth. We think there is a rocky interior – the core of Europa – that is in contact with this underground ocean. The interaction of water and stone is what produces the chemistry that you potentially need to live. We think this is how life began on Earth; at these mid-ocean ridges on Earth, where ocean water came into contact with rocks, heat and magma coming out of the Earth's interior.

Europa's energy is generated in its slightly elliptical orbit around Jupiter. This causes Europa to almost breathe or bend, and this bending generates a lot of heat in the rocky interior, and then it has to escape out. We think it's all been bubbling together for 4 billion years. And we don't know how long it will take for life to begin. It can be instant. It could be a billion years. That's why it's so important that we have this time component.

Any questions about habitability?

This has a lot to do with the stability and composition of the ocean. We think it's salty. We don’t know exactly what salts are there and whether there is organic matter there. It is a truly important chemical element for habitability. If you think about it, maybe life could have started and then it devours everything. And if these nutrients are not renewed, it will die. Therefore, within Europe there must be a cycle, a circulation of nutrients. And we think it may come from a young surface.

The surface of Europa is very young, about 100 million years old. The age of the Earth's surface is between 200 and 300 million years. We think there may be some entity of plate tectonics occurring in [Europa’s] ice shell, refreshing surface. Oxidants in harsh radiation environments actually produce oxidants at the surface, which can then be transported into the ice shell and then into the ocean. If you like, this could create a nutrient conveyor belt that helps renew the nutrients in the ocean that can support life.

What does this mean for us on Earth if life can exist on other planets, other moons?

This is such an amazing and big question: are we alone? And I think that's amazing both from a fundamental human point of view and from a very scientific point of view. We have one data point about life in the universe. We don't know if we are special and unique or if we are more common than we think.

If we think Europa is inhabited, we need to go and find out if it really is inhabited, right? And this has important consequences. If it is habitable, we may understand how life begins, and perhaps we are not alone in the universe. Or maybe life is really shared. And that would amaze me, wouldn't it? And if it is uninhabited, but we think it is inhabited, then perhaps we are missing something. We may not know how life actually began on Earth. We are missing some piece of the puzzle. And when you only have one data point about Earth, it's very difficult to understand how life starts, where it might arise, and therefore whether we're alone in our solar system or alone in the universe.

There is also the broader philosophical question of whether we understand life at all. Should life originate the same way it originated on Earth?

What are you most looking forward to opening?

I'm looking forward to answers to questions we don't even know to ask yet. We think we know something about Europe. But we're going to learn so much and discover so many things with this very capable and amazing spacecraft that I don't even know what those questions are yet.

This is a generational mission. We do this not only for ourselves, but also for the next generation. I still use data from Voyager 2 and Galileo, data that comes out 50 years ago and 20 years ago. We undertake missions like this not only for our own scientific curiosity, but also to create data sets that will be treasured for future generations. And this is also so cool to think about. It's an exciting responsibility. It's also a big responsibility to make sure you're creating data sets that will be valuable for future generations.